From the John Birch Society Coloring Book, 1962. (Photo: The New York Times archive)

In 1962, Barbra Streisand channeled all the emotional turmoil and lyric despair of an abandoned lover into what must be the strangest four minutes of pop music ever written. “Crayons ready?” she croons, “Begin to color me.”

The opening lines of the song, “My Coloring Book,” refer to that year’s fevered interest in coloring books for adults, much like the trend that has taken off recently. “For those who fancy coloring books/As certain people do,” Streisand sings, before asking listeners to fill her sorrowful life with equally sorrowful hues. When the song came out, coloring books for adults permeated pop culture, as Mort Drucker’s JFK Coloring Book spent 14 weeks at the top of the New York Times bestseller list in 1962, and sales of adult coloring books reached $1 million. Today, coloring books are perhaps even more profitable: Johanna Basford’s Secret Garden and Enchanted Forest were the two best-selling books on Amazon in April, responsible for some of the year’s recovery in print sales. (Basford has sold nearly 10 million coloring books since Secret Garden was published in 2013.)

But their powerful appeal—enthusiasts say they are a “great way to de-stress”—has very little in common with adult coloring books from the 1960s. Where today’s titles offer consumers a neat package of therapy, escape and nostalgia, 1960s coloring books were both genuinely novel and subversive.

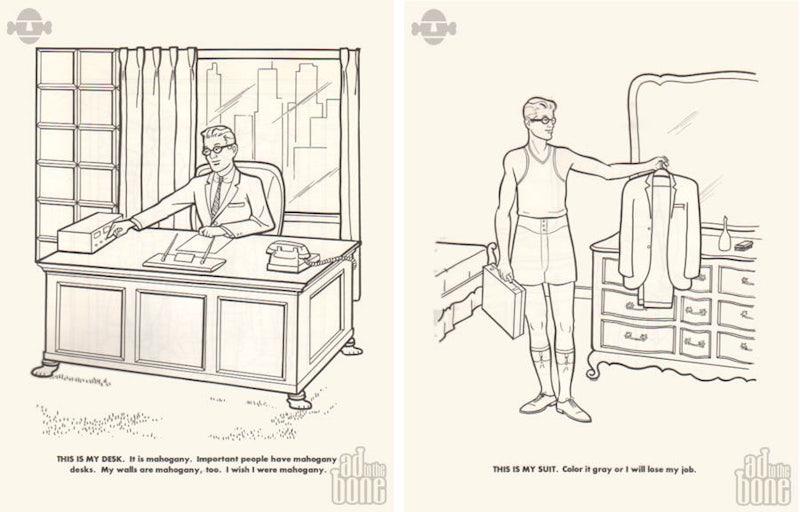

The first adult coloring book, published in late 1961, mocked the conformism that dominated the post-war corporate workplace. Created by three admen in Chicago, the Executive Coloring Book show pictures of a businessman going through each stage in his day, as though teaching a child what daddy does at work. But the captions, which give instructions on how to color the image, are uniformly desolate. “This is my suit. Color it gray or I will lose my job,” reads a caption next to a picture of a man getting dressed for work. Another page shows men in bowler hats boarding their commuter train. “This is my train,” it reads. “It takes me to my office every day. You meet lots of interesting people on the train. Color them all gray.” The rare appearance of a non-gray color is even more disturbing: “This is my pill. It is round. It is pink. It makes me not care.”

From The Executive Coloring Book, 1961. (Courtesy: Ad to the Bone)

The coloring books that followed managed to cover, between them, a selection of the decade’s neuroses: national security, the red scare, technology, sex, mental illness. Two popular books took aim at President Kennedy: Drucker’s JFK Coloring Book and Joe B. Nation’s New Frontier Coloring Book. There were coloring books that made fun of communists and coloring books that made fun of people who were scared of communists. Khrushchev’s Top Secret Coloring Book: Your First Red Reader caricatured Soviet leaders and life under communist rule, but was still deemed “objectionable” and banned in the United States Military. Meanwhile, the John Birch Society Coloring Book, which ridiculed conspiracy theorists and extremists, stretched the coloring book concept to its limits with a blank page, captioned: “How many Communists can you find in this picture? I can find 11. It takes practice.” In August 1963, theWashington Post reported on a doctor who proposed using a 12-page coloring booklet “as a diagnostic tool…to classify patients by their types of disorders” from schizophrenia to brain damage. The Post called it the “Psychotic’s Coloring Book.”

From the New Frontier Coloring Book, 1962. (Photo: The New York Times archive)

As the trend wore on, the books’ targets became more predictable. Publishers ridiculed occupations and lifestyles that already looked ridiculous without their help. The Bureaucrat’s Coloring Book, for instance, made fun of government commissions and regulations. The Hipster Coloring Book made weak jokes about the flatness of a supposedly daring lifestyle. The captions became more knowing and metaphorical. A picture of a smoking jacket-clad young man says: “He has a fun time… Color the gleam in his eyes brightly.” 1963’s Programmer’s Primer and Coloring Book made complicated jokes about bugs and core dumps with bizarre instructions to “Color me Mickey Mouse” and “Color him naïve.” They lacked the straightforward sadness ofThe Executive Coloring Book’s instruction—made sadder because so plausible—to “Color me gray.”

The captions, of course, didn’t need to be particularly clear, since they were never intended as real instructions for a reader with a set of crayons. The point of the sixties coloring books wasn’t to sit down and do some coloring, but to read their message and take a stand; they were more like a specialized form of political cartoon. (Supporters of Robert M. Morgenthau, in fact, used coloring book-style panels to lampoon Morgenthau’s opponent in the race for Governor of New York, Nelson Rockefeller, in fall 1962—Daniel Moynihan’s idea.) An article in The Daily Illini in September 1962 explains that although “the hottest item in publishing these days” is the coloring book for adults, they “aren’t expected to color it, however; just to look and laugh.” Similarly a New York Times’s trend piece from August 1962 reports that adult coloring books haven’t boosted sales of crayons. The only adult they spoke to who “insisted he colored every one of the books he could get his hands on,” it is drolly revealed, “works for a crayon company.”

Why, if people didn’t actually color them, did coloring books for adults exert such a pull on a generation’s imagination in the early sixties? One consideration is that coloring books—a nursery activity adopted by adults—exploded just as interest in Freudian psychoanalysis, and with it child development, was gaining unprecedented levels of popularity. Not only did coloring books show adults a childishly simple view of a corrupt world, they also showed how a child could be corrupted in the process of learning. When the child is instructed to color the executive gray, she sees the absurdity of conformism, but ultimately learns to take part in it by following the instructions. For adults, the conceit of a return to childhood offered the chance to reject the system and embrace entirely new principles; this questioning of the norms of America society would also stoke the emerging civil rights, anti-war, and women’s liberation movements.

Perhaps just as important though is that the generation that came of age in the early sixties was the first generation that grew up with wax crayons. Although crayons were invented at around the turn of the last century, they were expensive and not particularly sophisticated. A 1909 article in the Christian Science Monitor describes them as “one of the luxuries of the schoolroom.” It was in the 1930s that coloring with wax crayons really took off. By 1935, the manufacture of crayons and pencils was a $20 million industry—one that had grown by nearly 40 per cent in the two years since 1933. In 1934, the Chicago Daily Tribune reported on the crayons’ “gain in size color and tricks,” commenting on the assortment of “blue violets, yellow oranges, and other delectable colors” now available. Art education, a young discipline that was bolstered during the Depression by the Federal Art Project, hadn’t yet rejected coloring books as a useful tool in the classroom. That would come in the late 1950s when Viktor Lowenfeld, one of the most influential scholars of art education, claimed that coloring books had a “devastating effect” on children, by preventing them from “developing their own ideas.” The 1930s and 40s remained a golden age for coloring.

This fact might also have something to do with the demise of the political coloring book by the 1970s. Although newspapers would periodically announce revivals of the adult coloring book craze through the seventies and eighties, the “New Coloring Books,” as one writer called them, dealt in nostalgia more often than dissent. A 1974 Times article found Classics majors producing designs based on Greek vases and The Canterbury Tales. Their story also contains a lovely example of 1960s counterculture remnants being subsumed into consumer culture, as the Classics major explains their project’s origins: “When the underground comics scene sort of faded out here in San Francisco, we fell heir to some of the young artists working on them.” In the 70s, as today, the market for adult coloring book was driven by interest in simple, artsy pastimes. Recent politically-themed coloring books—Hillary: The Coloring Book and Trump 2016: Off-Color Coloring Book among others—have been relatively late additions to the latest crop, but neither their sales nor their cultural impact can match their therapeutic, decorative counterparts.

From Hillary: The Coloring Book, 2014. (Photo: Ulysses Press)

It’s improbable that coloring books will ever be truly subversive again—but that much has been clear since Barbra Streisand sang mournfully of “the heart that thought / he would always be true / Color it blue.” The fathers of the first coloring book craze were, after all, advertising executives, who knew that a gimmick was only good for one season, and had moved on by the next year to satirical cook books. Meanwhile, the activism of the twenty-first century has found its outlets more often online—in video and social platforms—than in the behemoth of print media. And it’s unlikely that future satirists will look back on coloring as something that was ever an innocent or uncomplicated activity. One of the most popular children’s books of recent years—it has spent two years on the New York Times bestseller list—is called The Day The Crayons Quit.

Welcome to No One’s Watching Week, the time of the year when the readers are away and your tireless editors have run amok. For this week only, Atlas Obscura, New Republic, Popular Mechanics, Pacific Standard, The Paris Review, and Mental Floss will be swapping content that is too out there for any other week in 2015. This article originally appeared on the New Republic.

Welcome to No One’s Watching Week, the time of the year when the readers are away and your tireless editors have run amok. For this week only, Atlas Obscura, New Republic, Popular Mechanics, Pacific Standard, The Paris Review, and Mental Floss will be swapping content that is too out there for any other week in 2015. This article originally appeared on the New Republic.