Nepanthes maximum, a carnivorous plant that eats insects (Photo: LadydragonflyCC/Flickr)

Once the idea of a giant, flesh-eating plant enters the imagination, it can be hard to dislodge. Imagine this: you’re in the jungle, and you discover a plant with surprisingly large, tentacle-like leaves. The clearing is full of a heavy, sweet smell. Maybe there’s an animal skeleton under the plant. Did the leaves move? Was that just the wind? You move closer, and the plant seems to yearn towards you….

Or this: in a grey European greenhouse, there’s a strange plant growing. No one has been able to identify it, and it’s yours to study. This could be your shot at botanical immortality; for now, no one needs to know that you’re keeping it alive with hunks of meat...

These are tales that get told over and over again–whether they’re about a “man-sucking tree” in east Africa or the Devil’s Snare in Central America, whether the strange plant is in a hothouse in England or a little shop of horrors in New York City. Like the carnivorous plants they describe, they’re very hard to kill off.

Is it comforting that no plant that eats humans has ever entered the annals of science? That even a rat is perhaps too ambitious a meal for any known carnivorous plant? It doesn’t seem to matter: people just keep inventing plants with a taste for human blood.

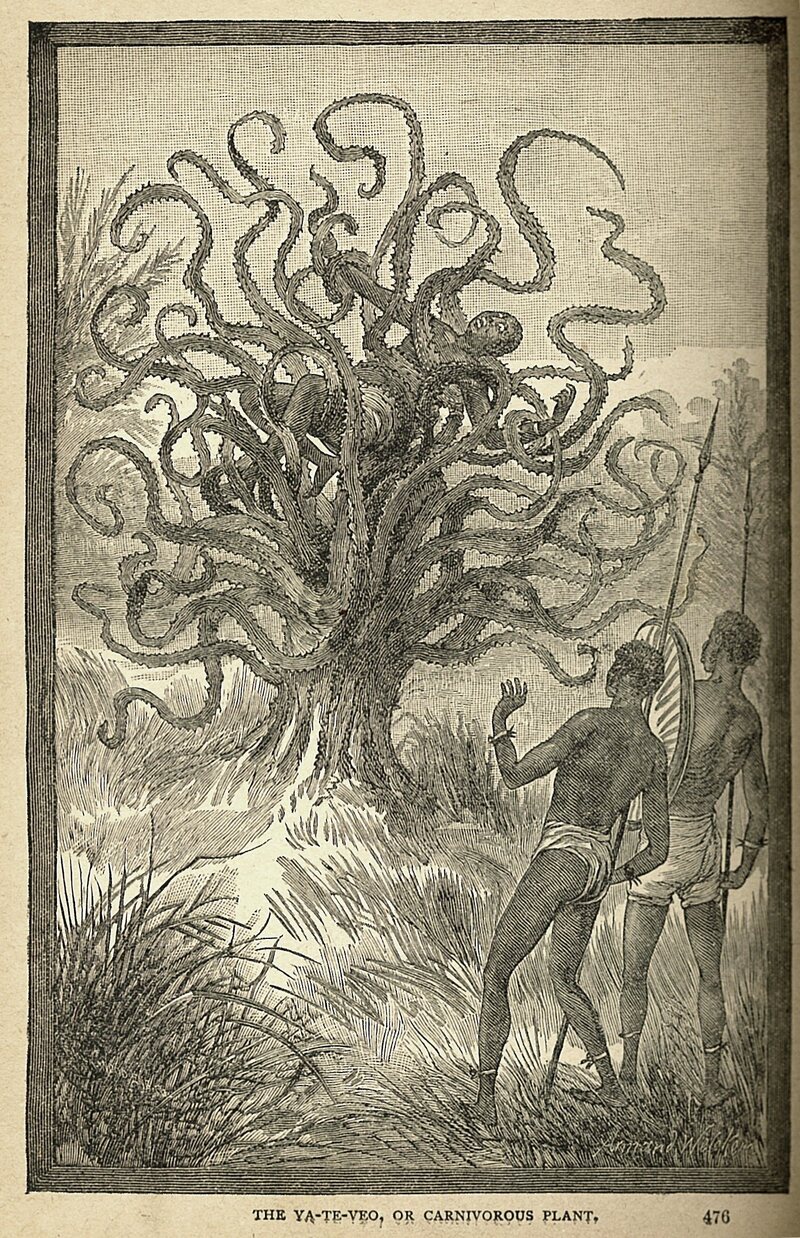

J.W. Buel's blood-sucking plant (Image: Wikimedia)

Stories of man-eating plants particularly flourished in the 1880s. Generally, an intrepid European in an unfamiliar place would encounter the plant and subsequently witnesses its carnivorous habit when a local stumbled into its grasp. Often, these accounts came second-hand. In Phil Robinson’s 1881 Under the Punkah Tree, for instance, the author’s uncle finds a tree with “great waxen flowers” and “great honey drops” of fruit, with leaves that open and close like tiny hands. A local boy runs into the thicket of the tree’s leaves while chasing a deer.

“There was then one stifled, strangling scream, and except for the agitation of the leaves where they had closed upon the boy, there was not a sign of life,” Robinson writes. J.W. Buel’s Sea and Land, published in 1889, includes stories from “travelers” about a plant with a thick trunk and giant spines, which squeezes the blood out of its victims until “the dry carcass is thrown out and the horrid trap set again.”

But perhaps the most gruesome man-eating plant tale came from an apparent first-hand account. In the popular press, a scientist named Karl Leche described encountering a plant with a base like a pineapple. It had eight long leaves, fat and spiky like an agave’s, and six white tendrils that moved languorously in the air. When a woman is sent to drink from the sweet liquid pooled at the plant’s top, the tendrils grab her, the leaves close in, and a mix of plant fluid and blood seeps down the trunk.

For a time, it wasn’t clear these stories were fiction. Buel’s account of the man-eating plant follows reports of a number of real, fascinating species–a bread-fruit tree, a pitcher plant, and a tree that produces poison used to tip deadly arrows. He does express doubt that the blood-sucking plant is real, but hedges. “Hundreds of responsible travelers declare they have frequently seen it,” he writes. The Leche story was published in magazines and newspapers as fact; it wasn’t until decades later that it was busted as a wholesale fabrication.

Why were people willing to believe in something so horrendous? Even if people like Buel doubted, they had to judge whether a blood-sucking plant was more unbelievable than some of the other reports that reached them. After all, awesome octopi existed in the ocean; why couldn’t a plant that grasped its prey with vegetal tentacles exist, too?

Darlingtonia californica, another real-life carnivorous plant Photo: NoahElhardt/Wikimedia

The actual reality of carnivorous plants is less dramatic. Plants need nitrogen, and in places where the soil is poor, they catch small creatures to provide that nutrient. Over 600 species of plants have evolved to consume insects and other living creatures; at least five different groups independently developed these strategies.

There is something gruesome about these plants, though. Pitcher plants, for instance, use a pool of somewhat acidic liquid to slowly digest the insects they trap. But their pitchers cannot expel waste.

“As it's getting older, it gets filled with a lot of insect parts. It can't digest everything,” says Tanya Renner, a biologist at San Diego State University who studies carnivorous plants. “There are exoskeletons leftover. It's sort of like a graveyard.”

Some larger pitcher plants have been known to consume rats. But an animal of that size is a huge meal for a plant, akin to a human trying to eat a whole cow. If a rat is an almost overwhelming meal, digesting a human is impossible.

Still, what would happen if a pitcher plant was fed part of a human–a finger, perhaps?

“It would be able to digest it to a degree,” Renner says. “But it's going to be in there for a long time.” And, as with insects, there might be leftovers. “I don't know how well fingernails would get broken down,” she adds.

Nepenthes Rajah, a very large pitcher plant (Photo: Wikimedia)

There’s a second strain of story, more clearly fictional, about plants with a taste for human flesh. In these stories, the plants have help. An introverted botanist is so captivated by the idea of having discovered a new species of plant that he secretly feeds the monster, until it turns on him and somehow succeeds in making him into a meal.

Little Shop of Horrors closely follows this template. Seymour, the shy plant store employee, treasures his blood-sucking plant, Audrey II, and feeds it ever larger portions of meat, until it grows too hungry to keep hidden. In some versions, the humans triumph by destroying the plant; in others, the play ends with a giant plant occupying the entire stage, having eaten basically every other character.

Ugh, Audrey II (Photo: KlickingKarl/Wikimedia)

It’s probably the most terrifying musical ever written, but it’s part of a longer tradition. Perhaps the most clear precedent is a story published in France in the 19th century, in which a Venus flytrap-like plant grows large by consuming masses of raw meat. The obsessed botanist keeps the plant secret, until his wife and a friend sneak into his conservatory. The plant’s tentacles begin to drag the wife into its maw; the friend saves her by hacking at its roots; the botanist dies because he’s so upset at losing the plant.

In John Collier’s 1930s version of the story, the plant enthusiast is consumed but doesn’t die, exactly; he is reborn as an orchid bud. But, as part of the plant, he’s powerless to stop his bad-seed nephew from ultimately killing him, by pruning the flower that contains his consciousness. The end of the story is chilling: “Among fish, the dory, they say, screams when it is seized upon by man...in the vegetable world, only the mandrake could voice its agony–till now.”

Sometimes, though, the plant lover survives. In H.G. Wells’ story of a blood-sucking orchid, the shy botanist is saved by his housekeeper. In a 1905 story, “Professor Jonkin’s Cannibal Plant,” by Howard R. Garis, the steak-loving plant tries to eat the professor. But the plant is foiled by a friend, who stuns it with chloroform and pulls the professor out before he reaches the plant’s pool of digestive juices.

All of these stories have essentially the same theme: they are about awkward people who love plants too much. In the end, the protagonists' fates are determined by whether they have built strong enough relationships with the people around them to be saved–if they care more about humans than plants, they tend to survive.