Men gather outside the National Anti-Suffrage Association headquarters in 1911. (Image: Harris & Ewing/Library of Congress Public Domain)

This morning—having spent the past week hopping between a jail cell, newspaper headlines, and the right-hand sides of various Republican presidential hopefuls—Kentucky clerk Kim Davis, who was arrested last week for refusing to sign and process marriage licenses for same-sex couples, has returned to work.

An elected official, Davis cannot be fired, so instead spent five days in jail as a consequence of defying orders. Though Davis's supporters have compared her to various civil rights heroes, better parallels might be drawn to those who doggedly threw in their lot with an outdated side. As the country, and Davis' constituents, wait to see whether she will do her job today, let us look back at some of those for whom an earlier America changed too fast.

Benjamin Franklin's Loyalist Son

Benjamin and William fly the famous lightning kite. (Image: Le Roy C. Cooley/WikiCommons Public Domain)

Benjamin Franklin is widely acknowledged as one of the fathers of this country. It's less well-known that he was an actual father, to William Franklin. Born out of wedlock but raised by the Franklins, William built himself an impressive military and legal career of his own, taking the occasional break to fly kites with his dad, or to write "scathing pamphlets against [Benjamin's] political foes," under the pseudonym Humphrey Scourge.

By his early 30s, William's hard work and connections had landed him the governorship of the colony of New Jersey. Soon after, his career was interrupted by a little thing called the Revolutionary War. William had studied law abroad in London, and was a staunch Britain-loving Loyalist. A talented governor, he nonetheless earned the ire of many of his constituents by enforcing the dreaded Stamp Act, informing on local patriots and "working tirelessly against the cause for independence."

William Franklin, circa 1790. (Image: Mather Brown/WikiCommons Public Domain)

All of this was eventually too much for his father, who cut ties with William in 1775. A year later, William was arrested by the newly independent Provincial Congress of New Jersey, whose legitimacy he refused to recognize. He spent the next few years in and out of prison, organizing Loyalist groups and rebellions and, possibly, revenge killings. In 1782, he was exiled to Britain, where he continued to agitate for the Loyalist cause until the Treaty of Paris ended things the next year.

Officially caught on the wrong side of history, William tried to reconcile with his father, who agreed to do his best to let bygones be bygones. But in his last will and testament, Benjamin gave his only son very little, writing that "the part he acted against me in the late war... will account for my leaving him no more of an estate he endeavored to deprive me of." William died in England in 1813. His grave is lost.

Pro-Slavery Union Soldiers

Union General Oliver Otis Howard was particularly tough on officers who tried to resign in protest of emancipation. (Image: Library of Congress/Public Domain)

Throughout the Civil War, the majority of the Union Army was made up of volunteers—people who were willing to donate their time, effort and lives to the various causes that inspired the conflict. But in the days after Abraham Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation, a number of soldiers began second-guessing their dedication.

"Some Union officers were so distraught by the changing war policies that they resigned their commissions shortly after Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation," writes Jonathan W. White in Emancipation, the Union Army, and the Reelection of Abraham Lincoln. Men who were enlisted also deserted.

"Many of the officers who resigned," White writes, "were arrested, court-martialed, and punished." F.G. Stidger, a record-keeper during the war, writes of a series of resignation notices from a particular Kentucky regiment that came through his office after the Proclamation. After the requests repeatedly failed to be approved, "the matter was dropped by all the Officers except Major [Henry F.] Kalfus," who sent his along a third time, explaining that "since the consummation of the Proclamation of President Lincoln for the freeing of the slaves of the South he declined to further participate." This request was returned with an order for Kalfus's arrest, and he was paraded before the rest of his regiment, dishonorably discharged, and marched out of camp at bayonet-point.

The Anti-Suffragist Who Changed His Mind

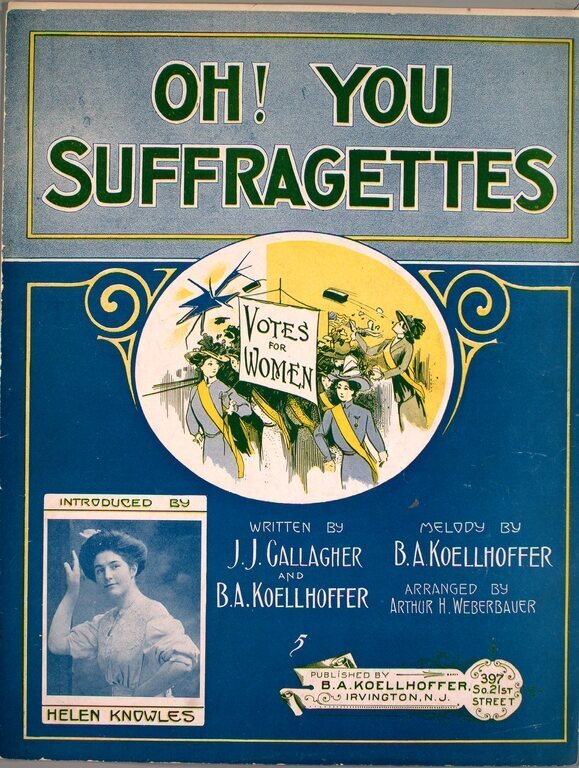

Don't you know you're driving your mommas and poppas insane? (Image: Levy Sheet Music Collection/Public Domain)

The women's suffrage movement built slowly. The 19th amendment that granted the right to vote was a hard-won victory, ratified by Congress 42 years after its original introduction. It made its way through the state legislatures until finally, in August 1920, it reached Tennessee, where it needed the support of 50 out of 99 representatives in order to be appended to the Constitution. Suffragettes and anti-suffragettes, swarmed Nashville, handing out different-colored roses that symbolized their positions—yellow for suffrage supporters, and red for those opposed. Citizens and representatives wore the roses to make their stances clear.

On August 18th, the day of the vote, the reds in the voting room outnumbered the yellows, and suffragettes feared the cause was lost. One of these roses was pinned to the lapel of Harry T. Burn, a 24-year-old representative from rural McMinn County. Burn had planned to vote "no" until he received a letter from his mother, Febb Ensminger Burn. After six pages of regular chit-chat, Mrs. Burns wrote to her son, "Hurrah, and vote for suffrage!... Don't forget to be a good boy and help Mrs. [Carrie Chapman] Catt put the 'rat' in ratification."

Burns brought the letter with him to the session. When voting time came, he went against his rose color and voted for suffrage. Legend holds that he then had to hide in the attic from an overexcited mob. He explained to the assembly: "I believe in a moral and legal right to ratify," but also "I know that a mother's advice is always safest for her boy to follow." In this case, his mother saved him from being the one man whose "no" vote kept half the population from voting at all.

George Wallace attempts to block integration at the University of Alabama on June 11th, 1963. (Image: Warren K. Leffler/WikiCommons Public Domain)

There are many more examples of Americans who failed to swap their roses, and stuck to guns doomed to backfire—George Wallace, the governor who tried to bodily prevent black University of Alabama students from entering a school building, comes to mind, as does Keith Bardwell, the Justice of the Peace who resigned in 2009 after refusing to grant marriage licenses to interracial couples. All were considered brave by those who agreed with them, and backwards-facing by those who did not.

But perhaps the best place to look is the first great work on this tactic: Henry David Thoreau's Civil Disobedience, in which Thoreau speaks to the local tax-gatherer, who he considers to be an agent of injustice. "If you really wish to do anything," he says, "resign your office."