Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Ominous skies don't bode well for migrating birds. (Photo: Unsplash/pixabay)

If it wasn’t already enough to fly thousands of miles—44,000 round trip, if you’re the Arctic tern—birds of all shapes, sizes, and flying styles are now facing increasing obstacles to migration. Warmer weather is shepherding in shorter winters and angrier storms, and there's recently been an upsurge in the frequency and intensity of hurricanes.

With shrinking winters affecting birds’ migration schedules, which start as early as June or as late as December, many birds find themselves awing during peak Atlantic hurricane season. While certain stormy winds can provide direct superhighways, and some birds may be able to harness a hurricane as a sort of slingshot to launch themselves forward at higher speeds, those are exceptions to the norm.

Caught up in storms, birds naturally seek out safety and shelter down on the ground. If they’re already in flight, they usually try to find an area with the least turbulent conditions and keep flying downwind. The less lucky ones end up battered on the beach or stranded and starved, with possibly hundreds of thousands of casualties after a major hurricane.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

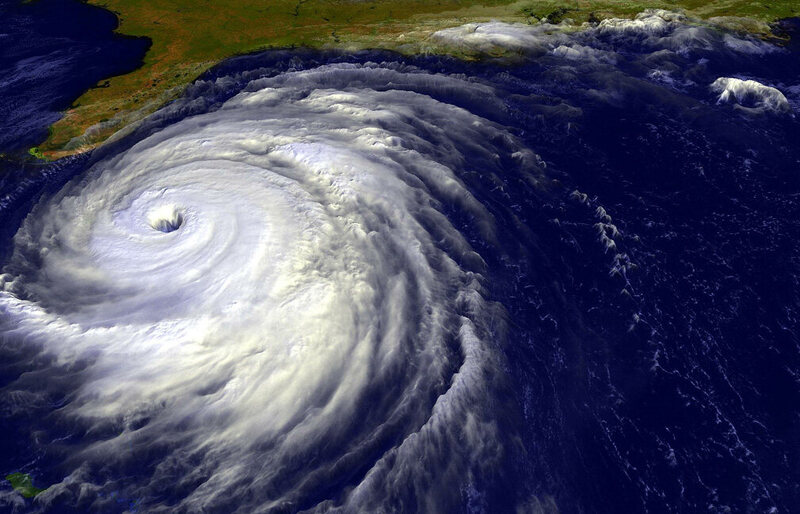

The type of winds that birds want to steer clear of. (Photo: WikiCommons/Public Domain)

Birds are some of Earth’s most talented navigators, using a suite of sensory modalities to orient and to navigate, explains Andrew Farnsworth of the Information Science Program at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, which runs eBird and BirdCast, two birding and migration databases.

“They orient with a magnetic compass, so to speak, which relates to the presence of a molecule in the eye that allows them to see the magnetic field,” he says. They’re orienting with celestial and solar, acoustic and visual cues as well. Some birds set off on their journey almost by the clock each year, while others base their departures more closely on local conditions. Routes and strategies differ greatly, in addition to time of day, frequency of pit stops, and modes of flight (such as soaring and flapping).

The increasingly evident and rapid climate effects in recent years, however, are starting to give migrating birds—which constitute 40 to 50 percent of all birds—a real run for their money. Increasing droughts force birds to reroute for sufficient food or face starvation, and unpredictable seasons mean unpredictable resources. Yet isn’t that the whole reason migration exists—to respond to changing climates?

Yes—but perhaps not one that is changing quite so quickly.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

The Sooty Tern, a seabird belonging to tropical oceans, can end up deposited as far as Europe after an intense hurricane. (Photo: WikiCommons/Public Domain)

“The idea that a changing climate in and of itself may adversely affect migration is not quite right, since the two are closely tied together,” says Farnsworth. “Speed and intensity are obviously the two key components here.”

Hurricanes are growing and evolving rapidly; in late October the Western Hemisphere saw its most powerful tropical cyclone ever measured with the arrival of Category 5 Hurricane Patricia near Mexico, which intensified in size and speed at a madcap pace. Fast-changing situations like Patricia are very challenging for migrating birds to deal with, says Farnsworth, and it’s not something that the birds may be able to perceive. Scientists are still working to figure out what happens when birds that weigh mere ounces get caught up in gale-force winds, where even the strongest flyers don't always have enough fuel to make it through.

The usual stormy elements—rain and wind, thunder and fog—are not new to birds, who are seasoned experts in weather management. Birds often fly through rain depending on how heavily it’s falling, though as water weighs them down, locomotion becomes inefficient. Some birds can coast along strong winds, but too much turbulence poses an issue.

Thunder and fog prompt a search for shelter, a search that can be extremely hazardous in areas with dense light pollution. Disoriented by the fog infused with city lights, birds will fly around for hours trying to figure out where to go, colliding with buildings and each other and dying in large numbers.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

A hurricane heading in to wreak some havoc and cause a lot of bird fallouts. (Photo: Roger W/flickr)

How capable are displaced birds at finding their way back on track? Could certain birds use storms to their advantage, to be transported to new habitats intentionally? Farnsworth says it’s difficult to know, as there’s a dearth of focused research, but it seems lost birds are not all that adept at re-routing. “It certainly seems that some species may use ‘bad weather’ like hurricanes to disperse, but this has never been proven,” he says.

Whether it’s intentional, bad luck, or a bit of both remains to be determined. Farnsworth points out that we already have trouble predicting where a hurricane is going to go, let alone the details of what exactly is happening to the birds inside of it.

As temperatures continue to rise, this is an area that is ripe for research. When thinking about migration itself as a response to changing climates, one hopes that the migratory birds we love will be able to adapt quickly to ever-shifting conditions.