Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

A Wild Male Turkey's mating dance. (Photo: Don McCullough/flickr)

Two men hovered over the turkey pen, watching. A large, male bird walked in a circle, readying his mating dance, keen for the right moment. The moment arrived–clueless and giddy, the bird excitedly fluffed his feathers and approached his object of desire: the severed head of a taxidermied, female turkey, mounted on a stick. It was the early 1960s, and Dr. Martin Schein and Dr. Edward Hale were working tirelessly at Pennsylvania State University to find out what makes domestic turkeys interested in sex.

They began with a taxidermically prepared female turkey model and a pen of active males. In order to learn what specifically gets a turkey visually interested in making more turkeys, the two men slowly removed parts of the turkey model, one by one. They detached the feet, the wings, and eventually the entire body of the taxidermied turkey until the stick-mounted head and neck, held like the grimmest puppet, remained.

In their paper “Stimulae Eliciting Sexual Behavior” the scientists write: “Male turkeys presented a body without the head displayed but did not mount. Presenting the head alone (upright) released display behavior followed by ‘mounting’ and copulatory movements immediately posterior to the head.”

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

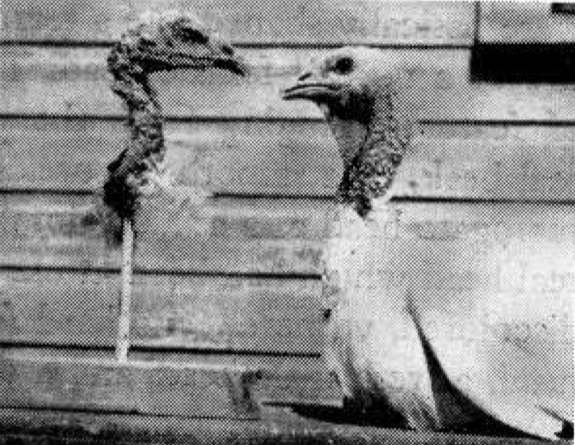

The taxidermied female turkey head, next to a live female turkey for comparison, from the study Stimuli eliciting sexual behavior by Schein, M.W., & E.B. Hale. (Photo: Schein & Hale, 1965)

The male turkeys didn't mind so much that the female turkeys weren't alive–in fact, they were fairly interested in balsa wood models as well. Schein and Hale decided that because turkey mating behaviors leave only the neck visible during copulation, the neck is the main stimulus, no matter where on the floor next to the “dilapidated body” it laid (including propped up solo on a custom-made stand). Schein and Hale were so intrigued by the success of this experiment that they repeated it with chickens in their paper “Effects of the Morphological Variations of Chicken Models on the Sexual Responses of Cocks”–chickens, if you're curious, apparently prefer hen bodies to the heads.

In another similar experiment, female and male turkeys were artificially induced into an early mating phase. The scientists put male and female turkeys in the middle of a room, and tested for their attraction to such objects as a turkey head mounted on wire, a human hand, and either “a small wooden block, an unlit lightbulb, or an inverted feed cup.”

The reason for all this hard work can't be chalked up merely to crazed scientific inquiry, can it? It seems like an awful lot of commitment for curiosity's sake. While it may seem like a useless, bizarre experiment from the outside, there may have been some logic to the methods Martin Schein and Edward Hale were using.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Turkeys in Sunol Regional Park. (Photo: Charlie Day/flickr)

In the wild, a male turkey's mating dance looks more like an old man's shuffle than a sultry display. The male puffs up his chest, pulls in his neck, and highlights his fanned tail, which he slowly moves toward the female turkey's gaze. He drags the tips of his wings on the ground between purposeful, tango-like steps, as the nearby female circles him until hopefully, she sits down.

In commercial hatcheries of the 1950s and 60s, however, farmers and poultry scientists depended on this dance. They noticed that captive turkeys began to breed less reliably over time–the number of hatched eggs was reduced. No one was sure what caused this, though, so poultry scientists began investigating every channel.

"Back in that time a lot of studies were being done on reproductive fertility,” says Phillip Clauer, of Pennsylvania State University's College of Agricultural Sciences. Part of the goal of those studies was likely to improve reproductive success in these birds, but also possibly to test the suspicion that a new phenotype of the domestic turkey were somehow more susceptible to fertility issues. "That's also around the time the pure white bird mutations were starting to show up," adds Clauer.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Heritage Turkeys on a farm in Maryland. (Photo: Curt Gibbs/WikiCommons CC BY 2.0)

Commercial turkeys, like wild turkeys, used to be brown–but due to normal genetic happenstance, a group of turkeys with a white feather mutation were born. As these new white birds grew, poultry scientists started to see a change in fertility, but the birds’ white feathers made them easily marketable. Brown feathers create colored splotches on turkey skin, and the lack of this meant a prettier product when selling the birds to the public as food. At the time, the reason for the low fertility problem in turkeys was speculative: genetic, physiological (fat turkeys have trouble getting into the right position), and hormonal issues were all listed as possible causes by Schein and Hale–but some factors, behavior and desire, had to be ruled out through analysis.

Understanding instinctive behaviors in other animals–think of the traditional rat and mouse experiments–gives us the potential to understand a model of how instincts and disease may work in other creatures, including human beings. Chickens with 'brittle cage disease,' for example, have already been used in osteoporosis research that might potentially benefit humans by further understanding the disease.

Experiments like those of Schein and Hale, which focus on a singular behavioral element, can help poultry scientists get to the crux of issues that arise in commercial and farm settings. For example, some current behavioral research includes how poultry see and sense light, and how light affects egg-laying, which lets farmers better regulate the domestic poultry environment.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

A baby turkey, or poult. (Photo: Kristie Gianopulos/WikiCommons CC BY 2.0)

More permanent solutions are possible with behavioral studies, too; some research increased the lifespan of farm-raised chickens by studying the violent tendencies alpha chickens naturally have toward birds low on the pecking order. “It used to be that cannibalism was a major problem [for domestic chickens],” says Clauer. “Over time they were bred away from those behaviors… a wild-type chicken is a nasty critter. Not a fun bird to be around.”

Similarly, by studying how turkey mating works, poultry scientists can learn how to alter or support different behaviors, be it through changing the birds’ environment or coaching changes through selective breeding.

It seems Schein and Hale weren't doing anything more bizarre in their experiments than going deep into the bizarre minds of turkeys. It's possible this sort of research will even help solve human problems of fertility and desire–hopefully, of course, using different methods.