In 1830, Stephen Preston Ruggles—an engineer and craftsman, and soon to take charge of the print shop at Perkins School for the Blind, in Watertown, Massachusetts—took on an unusual project. He got a map of Boston, pasted it to a thin wooden board, and began to cut. He traced around the city streets, slicing out Boston Common, the Charles River, buildings, and houses, but leaving in the city's roads, bridges, and squares.

Eventually, he had a kind of skeleton of the city, the streets separated from their surrounding environment. He glued this to a second board, which he had painted green. After what must have been hours of labor, he had what he wanted—a map of the nearest city that students at Perkins could actually read.

For centuries, people who were blind had no dedicated way to learn geography. But starting in the 1830s, at places like Perkins, educators repurposed existing technology—and invented new types of maps—in order to bring the world to their students' fingertips.

The Perkins Archives are filled with tactile maps from various eras. Many are like the Boston one—existing tools rejiggered for new needs. One has the Great Lakes cut out, pasted on a board, and heavily shellacked; another, a pastel map of Australia with borders and braille labels pressed into it. "You couldn't buy them in a store, so a lot of them are very experimental, says Jennifer Hale, the school's archivist. "They're very homemade, and very hard to date."

Others are more deliberate. In 1837, tired of what he considered to be partial solutions, Samuel Gridley Howe, the school's Founding Director, decided to take matters into his own hands. Enlisting Ruggles—who was doubtlessly eager for a way to map-make that didn't include painstakingly cutting out many square feet of bare space—he invented a new method of embossing maps, and released a book, the Atlas of the United States Printed for Use of the Blind.

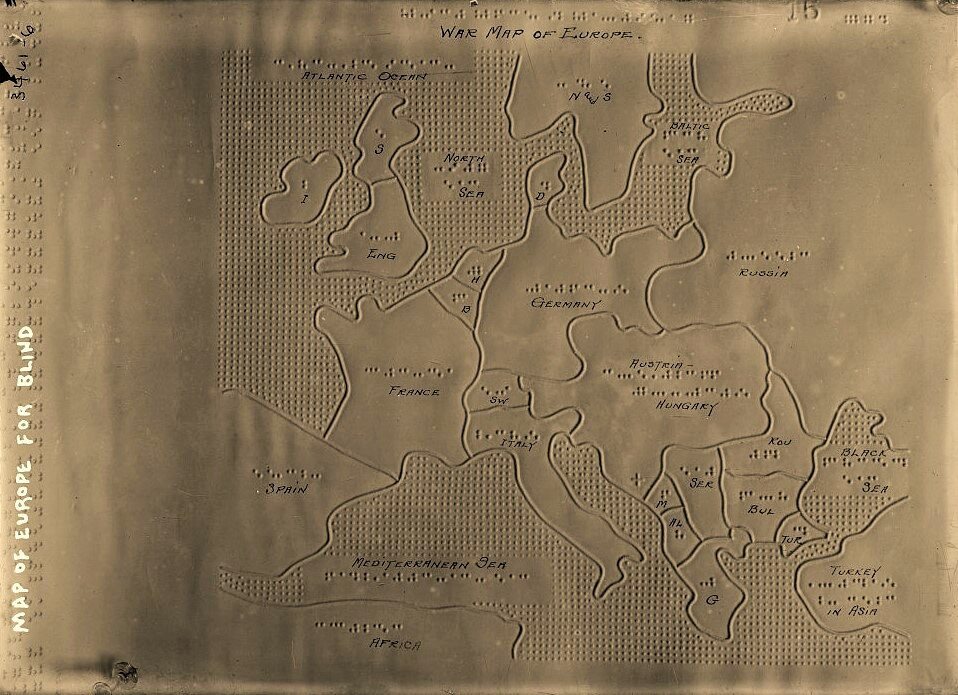

Like the writing systems of the time, these maps were raised above the paper, so that borders and contours could be easily felt. Textures denoted different geographical features, like lakes and seas. The maps contained labels and plenty of supplementary information, printed in Boston Line Type, Howe's preferred writing system. "It has been found a source of great pleasure and useful knowledge to the blind, who can study it unassisted by a seeing person," wrote Howe in the introduction to a later edition. This method was later used for mapmaking projects across the world, and the Perkins Archive is full of embossed maps.

That same year, Ruggles, who was in charge of printing at the school, undertook another big project—the Perkins Globe, a spherical tactile map made of 700 flawlessly glued pieces of wood. Likely the first globe in America made for people who are blind, the Perkins Globe is 13 feet in circumference and includes a set of moveable meridian lines. "The land is raised by a composition of emery firmly embedded in the wood; [and] the boundaries of countries, rivers, towns &c. have a very natural appearance," the Trustees of the Perkins School—then the New England Institution for the Blind—wrote in their 1837 Annual Report. "We believe this is the most perfect article of the kind in the world."

The Perkins Globe has undergone several restorations, the latest of which took place in 2004, when it was resurfaced and given a better support carriage. It is now on display in the Perkins Museum.

Puzzle maps, or "dissected maps," worked by a similar principle: students could take apart countries, continents, and hemispheres and piece them together again, learning how different states and regions fit together. While many of them were originally made for sighted students—the genre dates back to the late 18th century, and they were popular throughout Europe and the United States—they proved useful to blind students as well. "The best of all contrivances for imparting a knowledge of natural and political boundaries to the blind is the dissected map," the American Social Science Association reported in 1875, because "we cannot learn the shape of objects by touch alone unless we can embrace them or completely encircle them with our hands."

In the picture above, from 1893, two students in the geography room at Perkins are putting America together, state by state. The Mid-Atlantic, in pieces, waits patiently on the chair.

As anyone who has tried to freehand a map of their state knows, reading an existing map can only teach you so much. There's nothing like drawing your own to familiarize you with the placement of a capital city, or the ins and outs of a coastline. According to a contemporaneous account by educator Amelia Sanford in The Mentor, "map drawing" was invented in the 1890s, by the students and teachers of the Philadelphia School for the Blind. Noticing that her pupils loved making patterns on their leftover schoolbook pages, one teacher provided her class with blue denim cushions, different-sized furniture tacks, and wire. Taking her dictation, the students would mark out the outlines of states, countries and continents, and connect them with wire.

Familiar geographical shapes quickly emerged. "As the details were filled in, tacks of different shapes and sizes were used to locate cities, rivers, railroads, and mountains, and strings to mark limits of vegetation and productions," Sanford writes. "The class then journeyed in imagination through the different continents, filling in the details as they went along." The above map—made by Arthur Beckman, then a seventh-grader at Perkins—features Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont on maroon cloth, with green-pin mountain ranges, and the Penobscot and Merrimack Rivers in string.

Students also sculpted maps, which allowed for explorations in geology, topography, and even engineering. Nineteenth-century photos of the geography classroom show a sandbox, perfect for recreating an Andes-ridged South America, or sculpting a volcano. Some enhanced existing maps with 3-D borders and symbolic additions—like this "Production Globe," from 1927, which features imports, exports, flora and fauna. Others modeled new infrastructure proposals, like this bridge over Lake Champlain.

While there are many pictures of these sculptures and map additions, the actual items were probably wadded up and reused. "I haven't run into anything that has survived that is clay," says Hale.

These days, much map innovation for the blind is focused on inventing and enhancing navigational aids—making smartphone-savvy tactile subway maps, or personalized, 3-D printed building and neighborhood layouts. But these contemporary inventors are relying on technologies, such as embossing and sculpting, which were first brought to bear decades or even centuries ago by dedicated students and teachers. Looking through the map archives, Hale says "just impressed by the innovation of it all." "They're excellent examples of universal design"—just what you want when showing people their place in the universe.