In the 1800s, people were just as crazed about cats as we are today. But instead of memes, Instagram posts, and viral videos, the Victorians had satirical comics and chronicles.

English cartoonist, and evident cat fanatic, Charles Henry Ross wrote an epic encyclopedic book detailing the intricacies and culture of cats. InThe Book of Cats. A Chit-Chat Chronicle of Feline Facts and Fancies, Legendary, Lyrical, Medical, Mirthful and Miscellaneous, Ross makes an argument in support of the animal. Published in 1868, Ross read over 300 books, browsed newspapers, drew 20 illustrations, and gathered a mass of anecdotes about the fondness and repulsion towards cats.

The Book of Cats, he explains, is not “strictly zoological.” Rather, Ross says the origins of the cat-call, how people believed cats could predict the weather, and why some fainted at the sight of cats, among the collection of whimsical 1800s feline facts.

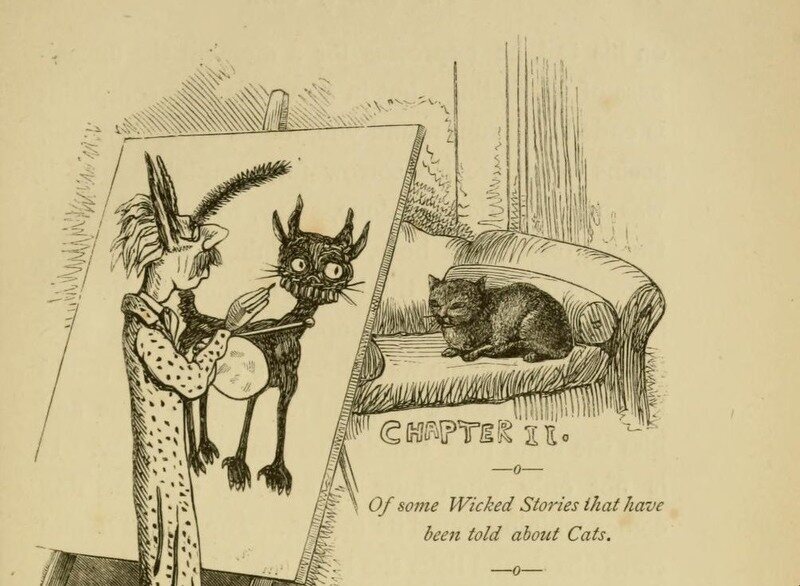

During the late 1800s, cats did not have the best reputation. While there were some like Ross who appreciated the furry creatures, many Victorians saw them as nuisances and “cruel” companions. When he excitedly told his friends of his plan to write a book about cats, they mocked his idea and argued that dogs, horses, pigs, even donkeys were better suited for a book. In his research, Ross found that many of the authors of cat books were prejudiced against the animal, and “knew very little about the subject.”

“Need I tell the reader who has thought it worth his while to learn anything of the Cat’s nature,” he writes, “that there are countless instances on record where Cats have shown the most devoted and enduring attachment to those who have kindly treated them.”

The Book of Cats addresses the wild, popular fears regarding cats—rumors flying that their scratches were venomous and that their breath sucked the life out of infants. In comparison to the smooth cut left from a knife, the thin scratch from a cat’s sharpened nail often festered, leading people to believe their claws were venomous, Ross explains. In addition to avoiding their claws, some would lose their wits at the mere sight of a cat. Conrad Gesner, a 16th-century botanist, documented men losing their strength, perspiring, and fainting when they saw a cat. A few have reportedly fainted after seeing a picture of a cat.

One of the most ridiculous accounts, according to Ross, were of cats accused of killing babies by stealing their breath. In 1791, the Annual Register published a story of an 18-month-old infant who died “in consequence of a Cat sucking its breath, thereby occasioning a strangulation.”

There were thousands of tales and numerous articles of the same vain, depicting cats as villainous, deathly creatures. However, Ross tries to clear up these rumors, quoting a friend and surgeon who stated that the anatomical formation of a cat’s mouth makes it impossible for it to suck a child’s breath. The surgeon proposed that if a cat were truly responsible, perhaps it’s feasible for it to lie over an infant’s mouth for the warm exhalations.

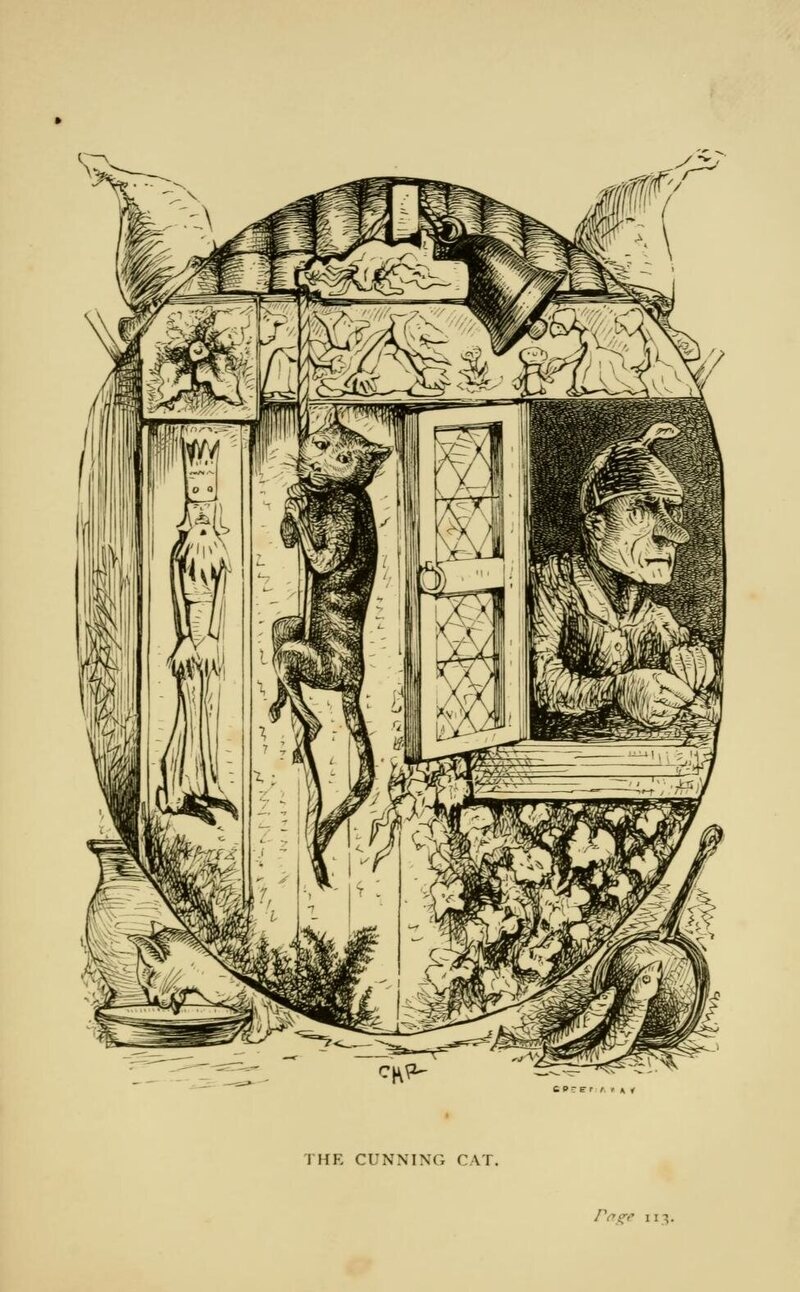

Beyond erratic fears, others believed cats had supernatural powers and psychic abilities. The Chinese reportedly used to peer into cats’ eyes to determine the time, while the playfulness of cats is said to indicate an approaching storm, Ross writes.

“I have noticed this often myself, and have seen them rush about in a half wild state just before windy weather.” People postulated that cats felt an irritation under the skin when it was about to rain, showing discomfort and unease.

He also details a method to feel shocks from a black cat, which were said to be highly charged with electricity. To produce the effect, he instructs the reader to place one hand on a black cat’s throat, while running the other down its back. One should then be able to feel the electric shocks on the hand on the cat’s throat.

Feline powers were also thought to help cure illnesses. Those who suffer from rheumatism often felt an improvement in their condition in the presence of a cat. There was a saying that collecting three drops of blood taken from under a cat’s tail, mixing it with water, and drinking it would cure epilepsy. Others thought the brain of a cat could cast someone under a love spell if taken in small doses.

The term “cat” was an integral part of 1800s language, with Victorians often referring to the animal in slang and proverbs. For example, “cat o’ nine tails” was the colloquial name for a kind of whip that branched into nine knotted cords. Used as a form of military punishment on soldiers and sailors, the whip produced lashes on the back that looked like claw marks. Salt miners used to call common granulated salt “cat-salt,” while the catkin flower got its name from the Dutch who thought the hanging rope shape was similar to a kitten’s tail. Not all cats are afraid of water—there was even a type of Norwegian ship called a cat, Ross says.

When someone was caught playing a trick, they may plea “cry you mercy, killed my cat!” to try and escape punishment. The French also had proverbs about cats, such as “elle est friande comme une chatte,” which means “she’s as dainty as a cat.”

Ross went to great lengths to clear up the cat’s reputation. Little is known about how many copies circulated of The Book of Cats or how receptive people of the 1800s were to Ross’s argument. While many of these superstitions and legends seem outlandish today, it reflects Victorians' fascination with one of our most beloved domestic animals—in addition to their mystery.