If you think about silent-film era sex symbols, you probably conjure up a mental picture of Rudolph Valentino—even if you don’t know his name. Valentino has become synonymous with sex appeal in early films. But he wasn’t the first male star of American movies to make millions of American women go weak at the knees. That distinction goes to Sessue Hayakawa, the Japanese star of Cecil B. DeMille’s cinematic rape drama, The Cheat.

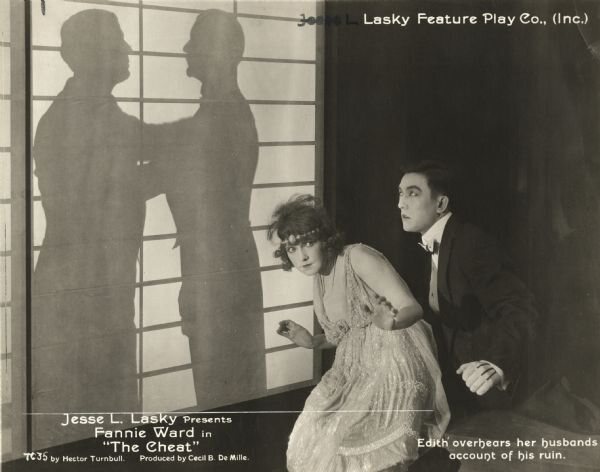

This 1915 film was a huge hit in spite of (or more likely because of) the fact that it lasciviously hinted at a taboo subject: interracial sex. The titular “cheat” (Fannie Ward) depicted in the film is a materialistic, dishonest tease. Hayakawa, who plays her neighbor, starts out as one kind of Asian stereotype (a polite gentleman), but turns out to be an entirely different one (a swarthy predator).

The possibility that an Asian man might be a more appealing sex partner for a white Long Island matron than her middle-aged Caucasian husband was too transgressive a notion for DeMille to fully commit to; he has Hayakawa, after spending much of the film chastely escorting Ward’s vapid socialite around, metamorphose rather abruptly into a sadistic rapist.

The Cheat made Hayakawa an international star. America’s teenage girls and swooning housewives fell for his charms, but French intellectuals like the novelist Colette and Polish-born filmmaker Jean Epstein sang his praises too. Film historian Daisuke Miyao begins his 2007 study of Hayakawa with the words of Miyatake Toyo, a Japanese photographer working in America in the early 20th century, who called Hayakawa “the greatest movie star in this century” and described a scene of female fans throwing their fur coats at the star’s feet to prevent him from stepping in a puddle. If People magazine had existed during the late 1910s, Hayakawa would have undoubtedly been declared the “Sexiest Man Alive.”

Hayakawa was born in 1890 to a wealthy family in Japan, and was expected to eventually work in the family fishing business. In his late teens, Hayakawa was sent to the University of Chicago to study political economy. Several years later, he drifted to Los Angeles where he began working in local theatre and abandoned his given name, Kintarō, in favor of the stage name Sessue (which was pronounced and occasionally even spelled Sesshū).

There, he met influential producer Thomas H. Ince, as well as a Japanese actress named Tsuru Aoki. Ince cast both Hayakawa and Aoki in his Japan-themed films, and in 1914, the two young actors married. The following year, The Cheat made Hayakawa a major star, and the Hayakawas became one of Hollywood’s golden couples.

Hayakawa remained popular for the second half of the 1910s, although he was often relegated to stereotyped non-white roles like "Chinese gangster" or "Indian doctor. In 1918, he formed his own production company, Haworth Pictures, in large part because of his dissatisfaction with the material he was being offered. He told a fan magazine the year after the release of The Cheat that the roles he had been playing “are not true to our Japanese nature….They are false and give people a wrong idea of us.”

The 1919 Haworth film The Dragon Painter, a kind of fairy tale about a mad Japanese artist searching for his manic pixie dream girl, is not devoid of stereotyping, but it at least tried to do something other than exploit the fear that Asian men constitute a threat to the purity of white women.

Around 1920, Hayakawa’s career started to falter. Miyao suggests that Hayakawa fell victim to a growing tide of anti-Japanese sentiment in the wake of the more-militant Japan that emerged after World War I. Hayakawa worked in Europe for a while, and then eventually returned to Hollywood a decade later. In 1931, he starred opposite Chinese-American actress Anna May Wong in the silly Fu Manchu talkie, Daughter of the Dragon. Although now in early middle age, Hayakawa was just as handsome as ever. Still, his heavy accent and his Japanese nationality made him a tough sell to the movie-going public.

Furthermore, Hollywood’s preference for white actors in all sorts of roles—including explicitly Asian ones—had a devastating impact on the careers of Asian actors. For example, Hayakawa’s sultry co-star Anna May Wong was an American-born native speaker who should have thrived in talkies. Nevertheless, she kept losing plum “Asian” roles to non-Asian actors, a common casting practice of the time that came to be called “yellowface.”

Indeed, when considering actresses for the film version of Pearl S. Buck’s prize-winning novel The Good Earth, MGM rejected Wong for the lead in favor of German actress Luise Rainer, who’d been unconvincingly made up in faux-Asian makeup. To add insult to Wong’s injury, Rainer went on to win the 1938 Best Supporting Actress Oscar for her performance as a Chinese peasant in the film.

Yellowface lives on, albeit without the garish greasepaint. This year, the makers of Doctor Strange stirred up controversy by replacing a character depicted as Asian in the comic-book source with the white actress Tilda Swinton. Something similar happened with the upcoming Ghost in the Shell, in which Scarlett Johansson will play a Japanese character—with a yellowface supporting cast.

It’s hard not to wonder: Wouldn’t it make more sense just to cast Asian actors? “It’s not that Hollywood can’t find talented people,” says Karla Rae Fuller, a film scholar and author of Hollywood Goes Oriental: CaucAsian Performance in American Film. Citing American audiences’ enthusiasm for the Asian actors in Ang Lee’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon—it was the highest-grossing foreign language film ever in the U.S.—she says that the Hollywood establishment may simply have a hard time imagining the appeal of minority actors. “On the level of logic, it makes no sense. But film is such a powerful medium, and the idea of giving minority groups starring roles, leadership roles—I think people shy away from that.”

San Francisco State University ethnic studies scholar Amy Sueyoshi notes that the Asian stereotypes of the past, including those that catapulted Hayakawa to stardom, have shifted in such a way that Asian men have been marginalized and even “emasculated.” While Asian women continue to be stereotyped as sexually available and desirable, Asian men have been desexualized, she notes. In the 1980s, Japan became an economic powerhouse, which made white Americans anxious about their country’s diminishing dominance, she says. In response, Asian men were stereotyped in pop culture as unmanly and unattractive—that is, not leading man material. (Think of the dorky foreign exchange student Long Duk Dong who crushes on Molly Ringwald in 1984’s Sixteen Candles.)

By the late 1940s, Hayakawa was nearing his sixties, but his age didn’t prevent him from enjoying a late-career renaissance in Hollywood. In 1949, he made Tokyo Joe with Humphrey Bogart and in 1950, Three Came Home with Claudette Colbert. Around that time Hollywood started to take a new interest in Japan—and Asian-Caucasian romance—leading to the release of films such as 1955’s House of Bamboo, directed by Samuel Fuller, and 1957’s Sayonara, about an Air Force fighter pilot, played by Marlon Brando, who falls in love with a Japanese woman.

Hayakawa appeared as a Tokyo detective in Fuller’s film, and shortly afterwards British director David Lean gave him the role he’s now best remembered for: Colonel Saito in the 1957 film The Bridge on the River Kwai. While Hayakawa was again asked to embody a racial stereotype—he played a cruel, inscrutable Japanese prison camp commandant—his performance is skillful and nuanced. Indeed, he was nominated for the Best Supporting Actor Oscar, although he lost to Red Buttons, a white actor in Sayonara, for his role as a doomed American soldier married to a Japanese woman.

Miyoshi Umeki, the actress playing Buttons’ Japanese wife, won Best Supporting Actress that year for her role in the same film. Those two nominations for Asian actors in one year was a fluke; since then, starring roles and film-acting awards for Asians haven’t been plentiful. In fact there have only been nine more Asian actors nominated for acting Oscars since Umeki’s win. The only Asian actors to have won acting Oscars are Ben Kingsley (Best Actor in 1982’s Gandhi) and Haing S. Ngor (Best Supporting Actor in 1984’s The Killing Fields).

The fact that Kingsley, who is of Indian descent, was already a successful actor in the U.K. before Gandhi suggests that Asian actors need to establish themselves abroad before getting a shot at mainstream American success. That’s certainly true of 2016’s honorary Oscar winner Jackie Chan, a Hong Kong action star who managed to parlay his homegrown popularity into a U.S. career. (Ngor’s case is one-of-a-kind; a non-professional when he landed the role in The Killing Fields, it was his real-life experiences as a prisoner of the Khmer Rouge that led to his casting.)

While attesting to the youthful Hayakawa’s electrifying presence at the height of his fame, photographer Miyatake Toyo wrote: “Never again will there be a star like Sessue.” It’s true that no Asian actor working in American film in the past century has been able to attain a similar level of stardom—and for that, Hollywood casting agents should be ashamed.