Clik here to view.

Say it's the mid-1800s, and you're on a beach in England. Things look pretty familiar: the wind tugs at parasols, children laugh and chase seagulls, the waves roll in and out. In the distance, though, an unusual figure straddles the water line, and stoops down over the sand. She's weighed down by enormous wool petticoats, and carrying a heavy bucket. From under her skirts peeks the unmistakable outline of a man's boot.

This woman isn't foraging for food, or trying to save a drowning child. She's one of Victorian Britain's many female seaweed hunters. Beloved by figures like Queen Victoria and George Eliot, seaweed-hunting became a popular way for women to tap into the enthusiasms of their era—and contribute to the burgeoning annals of science.

Nineteenth century Britain was a hotbed of biological enthusiasm. "Natural history was absolutely huge," says Dr. Stephen Hunt, a researcher in environmental humanities who works at the University of the West of England. Households filled up with painstakingly stuffed mammals and birds. So-called "gentlemen scientists" traveled the world drawing, describing, and collecting plants and animals. As railway networks grew, and labor advances led to more leisure time, ordinary citizens got in on the trend. Microscopes became more affordable, and collecting clubs popped up across Britain. "It was cross-class to some extent—working class and middle class," says Hunt. "There was a democratization of natural history."

Women, though, were still largely left out. The biggest natural history clubs of all, the Royal Society and the Linnaean Society, refused female members, and barred women even from their "public" meetings. Hunting animals was too dangerous, and digging up plants was, well, too sexy. "There was a taboo on botany, because Linnaean botany was based on the sexual parts," says Hunt. "That was seen as controversial."

Clik here to view.

Luckily, there was seaweed—docile, G-rated, and available somewhat close to home. "It was accessible for women in ways that other things weren't," says Hunt. As the seashore itself gained a reputation as a restorative landscape, plenty of women found themselves there, either recuperating from illness or seeking family-friendly summer fun. Many of them were already diehard scrapbookers, and seaweed makes a particularly rewarding collage subject: not only does each specimen's strange color and shape present a design challenge, its gelatinous inner structure means that, when pressed onto paper, it actually glues itself to the page.

While it's unclear exactly how many women spent their Saturdays kelp-crafting, there are enough amateur seaweed scrapbooks floating around to indicate that it was a popular pursuit. There is even one famous, long-lost scrapbook—Queen Victoria's, which she reportedly made as a young woman—and George Eliot has hinted that she dabbled, too, writing in an 1856 journal entry that the tide pools on the shores of Ilfracombe "made me quite in love with seaweeds." A number of collectors took their hobby to the next level, publishing descriptive guides complete with illustrations and collecting tips.

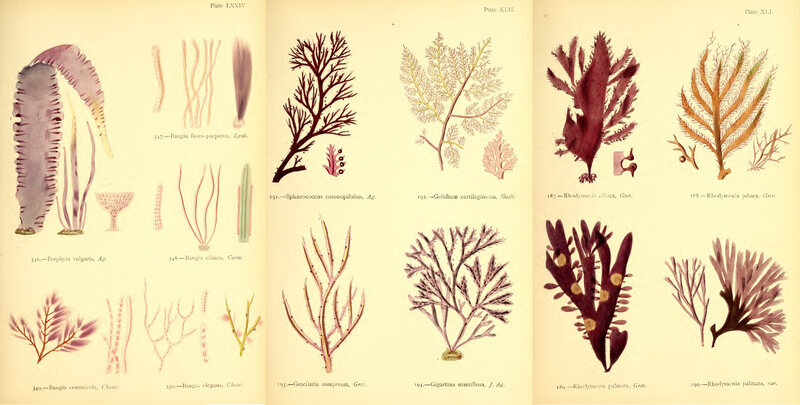

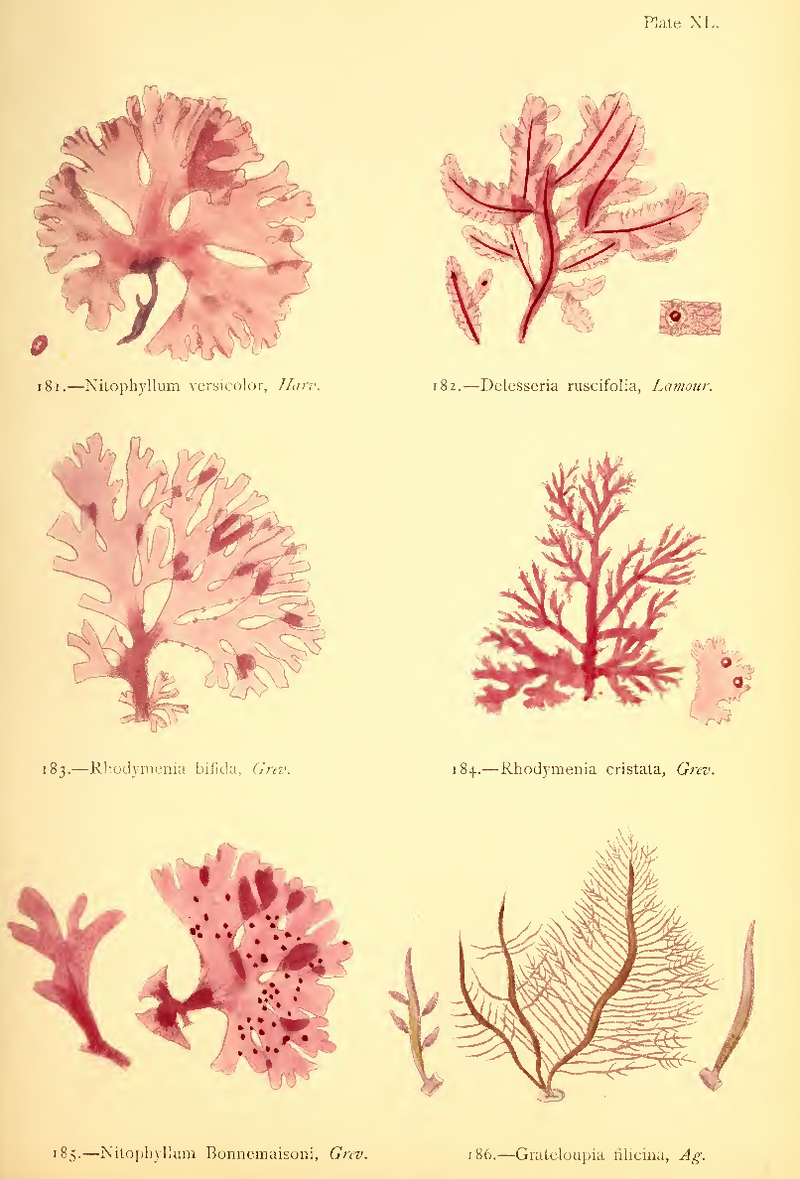

One of the best known and most dedicated of these so-called seaweeders was Margaret Gatty, a children's book author who took up the hobby while convalescing in Hastings, on Britain's southeast coast, in 1848. Gatty's crowning work of algology, British Sea-Weeds, is an exhaustive compilation of local seaweeds, fully described and illustrated in 86 colored plates.

Clik here to view.

But it's also a primer for women who might have been wondering how to align their exciting new hobby with the conventions of the time. In an opening section on how to dress, Gatty endorses a compromise between practicality and social acceptability. Wear your regular outdoor ensemble, petticoats and all, on top, she suggests—they are "necessary draperies." But definitely, definitely go for men's boots, and own it. "Feel all the luxury of not having to be afraid of your boots," she writes. "Feel all the comfort of walking steadily forward, the very strength of the soles making you tread firm."

Companionship was another issue. While women were given slightly more leeway at the shore than in the city, it was still seen as a dangerous place, full of slippery rocks and impending waves. "A low-water-mark expedition is more comfortably undertaken under the protection of a gentleman," Gatty wrote. How to convince one of them to go with you, rather than heading off on his own more risky or risqué natural history adventure? Offer up other enticements: "He may fossilize, or sketch, or even (if he will be savage and barbaric) shoot gulls," she recommends.

British Sea Weeds is an impressive work—two volumes, comprising 200 specimens, compiled over the course of 14 years. But like her female peers, Gatty made sure to position herself not as a scientist but as a kind of evangelist, interested in seaweed primarily as a low-level expression of nature's beauty and God's grace. "A lot of the women writers were sort of self-deprecating," says Hunt. "They very much saw themselves as popularizing natural history, but they took pains not to come across as professional scientists."

Gatty, who once wrote that hearing a woman give a speech was "like listening to bells rung backwards," planted herself firmly in her prescribed social role.

Clik here to view.

Privately, though, she found a certain escape in her hobby: "A love of routine makes in private life half the world commonplace and dull," she wrote to her sister-in-law, encouraging her to try out seaweeding. "Your seaweed hours will be a sort of necessary repast to you!"

For Gatty and others, the prioritization of religious rhapsody over rigor, combined with the heady freedom of the hunt, led to magnificent written reports—many of which remain more accessible than the dense taxonomies of their male peers. In British Sea-Weeds, one specimen is "delicately membranaceous," while another is "crisp and somewhat rigid when first gathered." Colors are lovingly described: "the finest crimson," "rose-red," "pinky towards the tips."

All fads eventually dry out, and as the Victorian era gave way to the modern one, fewer and fewer British women spent their spare time on the shore, feeling good in their galoshes and casting around for bits of red and green. Gatty herself never wavered in her enthusiasm, and kept collecting until her death in 1873. Although British Sea Weeds is now long out of print, her collections survive at St. Andrew's University in Scotland, where, over the past few years, curators have begun to restore and reorganize them.

Today's seaweeders would do well to look out for Gattya pinella: a species of Australian algae, named for one of the many woman who successfully found joy in seaweed.