Travis and Ingram's house (Photo: Dragonfly Hill)

In 2012, Steve Travis and Jeff Ingram buried their house. At first, it looked like a dirty mound until Jeff, the gardener of the two, got some wildflower seeds and meadow grass seeds and, together, they planted the roof. Slowly, the flowers and grasses grew up, and the house, still buried, started becoming really beautiful.

“Now, of course, we have to mow the roof, which is kind of a weird thing,” says Travis.

When Travis and Ingram explain that they’re building an earth-sheltered house, a type of underground house, most people think that they’ve living in a cave. But it’s not like that. The south side is almost entirely window, and on the east and west sides, too, there are big arched windows. At certain times of day, the light streams right through the house, from one end to the other.

From the outside, though, the house is camouflaged by soil. The design represents a longtime dream for the men, who got married recently after being together for 25 years. They wanted the house to blending into the environment, and this type of design, they decided, was one of the best ways to do that. And, sunny as the house is, being inside does feel like living underground, in a way. “You can kind of get the sense of the mass of the house that’s around you,” says Travis. “It’s not imposing, but it’s...I want to say womb-like. It’s very comforting.”

Inside Travis and Ingram's house (Photo: Dragonfly Hill)

Humans have been building underground housing for millennia; in northern China, cave dwellings date back to the second millennia B.C., and millions of people live still in earth-sheltered houses. Underground housing started out simple, like the dugout house that the Ingalls family moves into, on the banks of Plum Creek, in the Little House series, with vines of flowers framing the door, a thick sod wall fronting it, and a grassy roof that, as Laura Ingalls Wilder wrote, “No one could have guessed...was a roof.”

These days, there are houses built underground in former missile silos, and “iceberg” houses, where beneath a normal-sized house, extensive, luxurious basements might contain everything from bowling alleys to swimming pools. But in America, there are also some thousands of more modest underground houses. Relative to the Ingalls’ one-room sod house, these are sod mansions. But in the scheme of American ostentation, they are among the houses most gentle to the environment that they’re built in and also some of the longest lasting. While suburban McMansion might not last the decade, some of these earth-sheltered houses could be around thousands of years from now.

Ancient cave dwellings in China (Photo: pfctdayelise/Wikimedia)

Underground housing in America would not exist in its present form if not for Malcolm Wells, an architect who grew up in southern New Jersey and migrated later in his life to Cape Cod, Massachusetts. At the beginning of his career, Wells was a conventional architect, whose most prestigious accomplishment was his work on the RCA pavilion at the 1964 World’s Fair. Not long after that, he looked at the work he was doing and its destructive and transient nature, and he developed a new philosophy of building, which he called “gentle architecture.”

“What would happen if roofs and wall slopes became places for things to grow instead of places for cracked asphalt and graffiti?” he wrote in a book outlining his ideas. “What if architects routinely brought dying land back to good health?”

Underground architecture was not the only strategy he saw for achieving this, but it was one of his most original ideas. While not the only way to build without the destroying the land, “it’s simply one of the most promising (and overlooked) of ways,” he wrote. Here’s how he explained it:

(Image: Malcolm Wells)

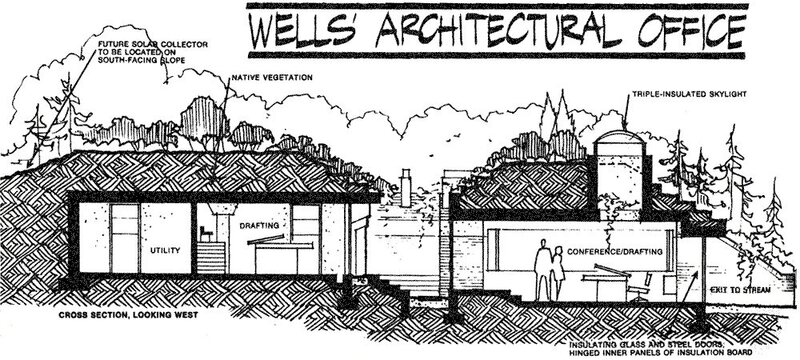

One of the first underground buildings he designed and built was his own office, in Cherry Hill, New Jersey, just outside of Camden.

(Image: Malcolm Wells)

From the entrance, it almost looks as if there’s nothing on the lot.

The entrance to Wells' office (now occupied by a PR company) (Photo: lamidesign/Flickr)

But that path cuts down into the ground, until it ducks under an entranceway, and into a garden. It’s almost like entering a hidden world.

“Malcolm Wells popularized earth-sheltered housing,” says Rob Roy, the author of Earth-Sheltered Houses and a designer, too. “He gave so many good reasons for building an earth-sheltered house and green roof.”

Earth-sheltered housing, as it came to be called, has a number of aesthetic and practical advantages. A living roof creates a landscape, instead of the tar sea of a shingled roof. And tucking a house into the ground, whether it’s covered with earth or not, helps the house blend more seamlessly into its site, preserving more of what was attractive about the land itself, before people started to mess with it. On a practical level, pushing piles of earth against the sides of a building means that the temperature just outside changes less dramatically than if the building is exposed to the air. While in some climates, outside temperatures might fluctuate from below freezing to almost unbearable heat, the temperature of the ground stays in smaller range, between about 40 and 70 degrees Fahrenheit. It takes less energy to heat and cool an underground house than a traditional house: it’s essentially like building a house in more advantageous climate than the one you’re actually living in.

These qualities were particularly appealing to environmentally minded innovators in the 1970s through about 1985, in what Roy calls “the halcyon days of earth-sheltered housing.”

“Back in the 1970s, when we had a president in the White House who would put on a sweater, underground housing became very popular,” he says. There was an oil crisis, after all. Fortuitously, a small handful of architects (including Frank Lloyd Wright, who wrote that “the berm-type house, with walls of earth, is practical — a nice for of building anywhere: North , South, East, or West”) were experimenting with these designs when the gas prices jumped and interest in energy-efficient housing rose.

Don Metz, an architect in New Hampshire, built his first earth-sheltered house after he came across a beautiful piece of land with a “killer” southern view. “The idea of putting a wedding cake up there got to me,” he says. “I started thinking about how I could minimize the impact of the house I wanted to put there, and it just evolved, to the thought—why don’t I tuck it into the earth? There wasn’t much literature at the time, so I essentially invented the details myself.”

When the oil crisis hit, the work he had done became the object of intense interest. “I got invited to symposia, and it was a happening thing,” he says. He’d hear from clients who wanted him to design and build this exact sort of house. But then, over time, interest tapered off. “The phone stopped ringing with that particular type of call,” he says. “The public seemed to abandon it.”

Metz' Treadwell House (Photo: Courtesy of Martha E. Diebold Real Estate)

Still, for a time, there was a groundswell of interest: Wells wrote that there were 15 or 20 architects who would regularly build underground, and that 25,000 people interested in underground architecture had written to him. In that period, too, these architects worked through some of the technical difficulties of building underground houses that were properly insulated and waterproofed. They laid the groundwork for today’s builders of underground houses, who have made the process more efficient and cheaper for the small group of people who choose to live inside the earth.

Today, a few companies around the country specialize in earth-sheltered housing. Generally, they offer customizable designs, and will sell the plans, along with an interior metal structure. Often, these houses, like the one Travis and Ingram are building, are created by spraying concrete onto a metal skeleton, waterproofing the resulting dome, and spreading earth on top and to the sides. They can be small, cabin-like structures—or they can be quite large.

“We’ve designed buildings based on our 24-foot model, that are 700 to 800 square feet, like a hunter’s cabin,” says David Skinner, the president of Performance Building Systems. “We’re also in the middle of designing a winery, that’s going to be huge, 32 by 120 feet, and a residence that’s going to be 7,000 square feet. The range is crazy.”

The range of people for whom they build, too, is wide. “We have people who are extremely green and we have people who you’d identify as preppers, and everything in between,” he says.

There is, though, a certain quality that draws together the people who want to build underground. “It tends to draw romantics and dreamers,” says Metz.

Allan Shope's earth-bermed house (Photo: Durston-Saylor)

Allan Shope, an architect in the Hudson Valley, used to design large houses for the rich and famous, but now he’s focused on projects of the type where he can take his client out to their site at dawn, sit in silence for 20 minutes and later ask them what they saw, what they heard, and what they think that says the design of their house should be. He’s built six or seven earth-sheltered houses, including the one he lives in.

“We didn’t want to make a big statement to world,” he says. "We love the integration of landscape and architecture, so that the landscape overwhelms the house, so that the house feels subservient to the land.”

Inside Allan Shope's earth-bermed house (Photo: Durston-Saylor)

More than any other “green” reason for choosing an earth-sheltered house, it’s the blending of the existing place and the new home that makes underground housing worthwhile. Now, it’s possible to build an energy-efficient house in all manner of ways: the LEED system is essentially a mix-and-match template for building an environmentally acceptable building. Earth-sheltering’s only real advantage is that it prioritizes preserving some sense of the land itself.

But these houses still do have a bunker-like aspect to them. They do well in tornados, so the actual house doubles as a storm structure. And, built of concrete, they have an estimated life span of hundreds of years. “There are no gutters to clean, it’s essentially fire-proof, it’s earthquake-resistant,” says Travis. “Anything short of a bunker buster bomb, I would survive.”

“There’s concrete 4,000 years old that's exposed,” says Skinner. “This is not exposed. We have no clue how long these will last. They could around five to ten thousand years, for all we know.”