There used to be parties in the apartments on the top floors of New York City's branch libraries. On other nights, when the libraries were closed, the kids who lived there might sit reading alone among the books or roll around on the wooden library carts—if they weren't dusting the shelves or shoveling coal. Their hopscotch courts were on the roof. A cat might sneak down the stairs to investigate the library patrons.

When these libraries were built, about a century ago, they needed people to take care of them. Andrew Carnegie had given New York $5.2 million, worth well over $100 million today, to create a city-wide system of library branches, and these buildings, the Carnegie libraries, were heated by coal. Each had a custodian, who was tasked with keeping those fires burning and who lived in the library, often with his family. "The family mantra was: Don’t let that furnace go out," one woman who grew up in a library told the New York Times.

But since the '70s and '80s, when the coal furnaces started being upgraded and library custodians began retiring, those apartments have been emptying out, and the idyll of living in a library has disappeared. Many of the apartments have vanished, too, absorbed, through renovations for more modern uses, back into the buildings. Today there are just 13 library apartments left in the New York Public Library system.

Some have spent decades empty and neglected. "The managers would sort of meekly say to me—do you want to see the apartment?" says Iris Weinshall, the library's chief operating officer, who at the beginning of her tenure toured all the system's branches. The first time it happened, she had the same reaction any library lover would: There’s an apartment here? Maybe I could live in the apartment.

"They would say, look, just be careful when you go up there," she says. "It was wild. You could have this gorgeous Carnegie…"

"And then… surprise!" says Risa Honig, the library's head of capital planning.

"You go to the third floor…"

"And it's a haunted house."

The exterior of the Fort Washington library the year it opened, 1914. The top floor windows are for the apartment. (Photo: New York Public Library/Public Domain)

The downstairs of the Fort Washington branch of the library feels big and bright. The Carnegie libraries have tall ceilings and sweeping windows meant to keep the buildings light and cool; each of the bottom two floors is an open, book-lined space, and on the second level, several giant, colorful lampshades float over the children's section.

A low wooden gate stretches across the base of the wide stairway that leads to the next floor. Walking up that last flight feels like fading into a different building. A water stain darkens the wall, and the etched steps are dusted with the chips of peeled paint fallen like dandruff from above.

At the top, the stairway opens into a large, shabby room with high ceilings. To enter, you pass through a well-crafted wooden frame of what was once a wall; now there is empty space where the door and windows were. The front room is brown and full of the textures of abandonment—the walls and ceiling look like they're sloughing off dead skin. Once, the library hosted performances in this space, and dances, but now the prettily molded ceiling is covered partway with rectangular metal chutes.

Fort Washington, the front room.

Fort Washington, the ceiling.

The apartment is reached through a smaller door by the staircase. Inside it, there's a long, dark hallway stretching down the length of the building. The room to the right once had generous windows, two, on the far wall. They looked onto the library roof. Now, in their places, there are walls of concrete bricks that block out the light but also unwanted visitors.

Even without lights to turn on, it's clear that the last family that lived here, probably a quarter-century ago, tried to make the apartment bright. The walls are painted in vibrant blue and yellow hues; the flooring in one room, now half torn away, is diamond-patterned with green and pink. No surface that could be decorated is left plain.

Inside the apartment, looking past the living room and kitchen doors.

Paint peeling.

The back bedroom.

The apartment doesn't feel haunted, exactly, but lonely and left behind. There is, however, a mysterious black door, with three sections, and a row of bells alongside it. No one knows where it leads, and it's jammed shut. It's the sort of door someone opens at the beginning of a horror movie that releases a demon or hungry creature.

Wrenched open, the middle section reveals a wall, brown and textured like washed-up seaweed. It's the back of a shaft. Look up, and there's a plate of glass keeping the rain out. Look down, and the hole plummets to the basement.

Death shaft, looking up.

Death shaft, looking down.

Death chute aside, this would have been one of the nicer library apartments to live in. Often the flourishes that made the Carnegie libraries special—the large windows and decorative moulding—were left out of the custodial apartments, but this one has some nice details.

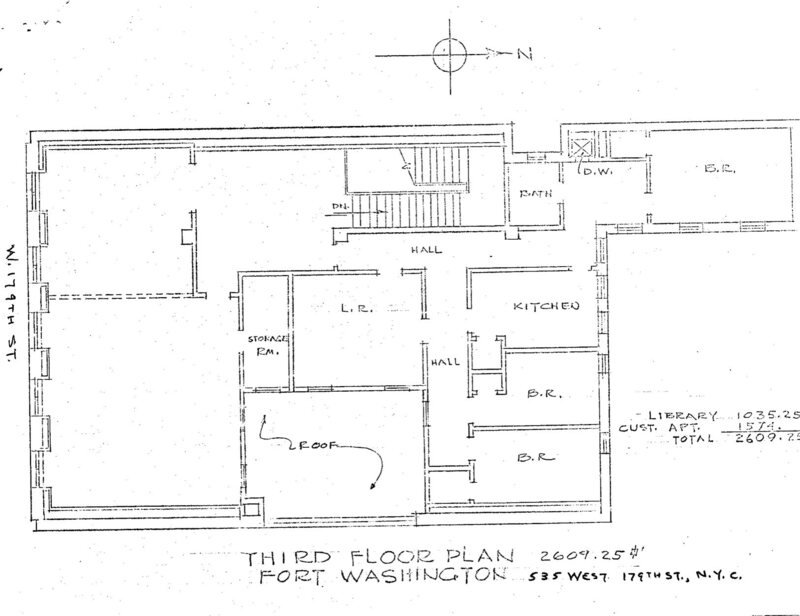

The apartment is larger than the others, too. Take a right at the kitchen, and there are two more bedrooms; go past it and there's another room in the back. Here's what the plan looks like:

Fort Washington plan. (Image: New York Public Library)

In that back bedroom, a small, dirty mirror is still hanging on the wall, at eye level. If it were my room, this where I might stand to apply mascara. Two dusty decals are still stuck to the door: one for the Muppet Movie, one that warns others to "Knock Before Entering."

In the kitchen, where the walls are covered with a stone-mimicking wallpaper, there are other remnants of previous lives—a Polaroid of a Christmas tree and a pirate-themed card, addressed to David J from William J, that reads: “You're a real treasure to me.”

Fort Washington kitchen.

Fort Washington.

Another bedroom, used for storage.

In today's New York real estate market, this apartment is not unappealing. Yes, it would need cleaning and modernizing before anyone moved in. The one toilet in the apartment is facing into a corner. But the rooms are large enough, the kitchen could fit multiple people, and it's in a library. Finding this much empty space anywhere in Manhattan is a rarity; walking upstairs in a well-used building and finding an empty floor feels like being in on a great secret.

For the library, though, these apartments are a waste, almost an embarrassment. They were built to serve a particular function, when libraries could survive on just lending out books. Now, when many libraries are reinventing themselves, their physical spaces must transform, too.

"We have so many demands on our space, besides just the books, that it’s almost criminal not to turn these apartments into program space," says Weinshall.

Fort Washington, in the kitchen.

Fort Washington.

Even the flagship 42nd Street building once had an apartment in it, occupied by a superintendent who had been a bootblack, bartender, Harvard man, boxing instructor, and a designer for Thomas Edison. The family moved out in 1941, because the library needed the space for a mimeograph room, telephone switchboard, and smoking rooms.

At Fort Washington, now, the library's programming room is a dark and narrow space on the second floor. After school, when the kids and teenagers arrive, the bottom two floors fill up fast. The teens have to stay on the first floor, with the adults; after-school tutors clash with parents over the proper noise level. There's no elevator here, either, so when parents bring their kids for story time, the entryway is crowded with a phalanx of strollers.

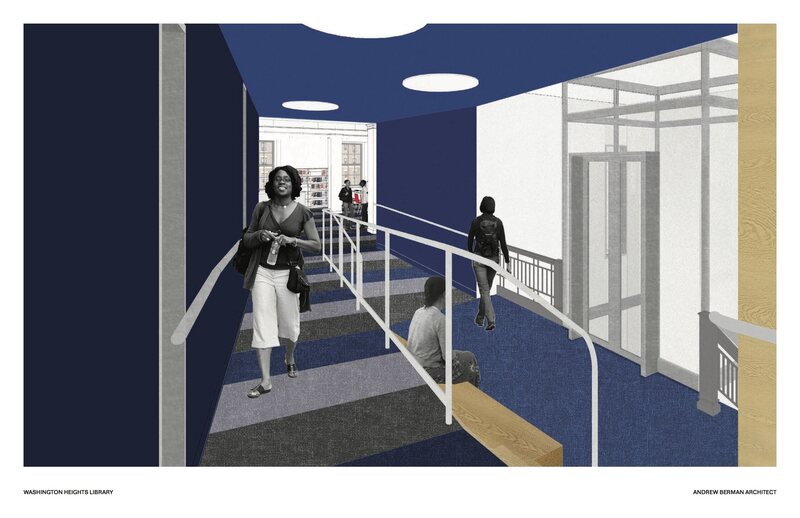

That's why the library is renovating the apartments, one by one. Not far from Fort Washington, at the Washington Heights branch, the third floor is almost ready to re-open. The glass elevator opens on a newly painted hallway, a bright blue not so different from the color in the dark apartment. In the ceiling, the white circles of new fixtures create pools of light. The front room has the same expansive quality as Fort Washington's, but this one is newly white.

A mock-up of the Washington Heights renovation. (Image: New York Public Library)

The apartment here was vacated more recently; there are still people on staff who remember Mr. Adams, the last custodian, and even after he left, employees would come up here to use the bathroom and even the claw-footed tub. Now, though, the space is divided into smaller, anonymous rooms; the kitchen has a brand-new fridge.

The renovation here is not quite finished, but the rooms look nice. Practical. The floor feels like any new space in 2016. It would be hard to tell anyone had ever lived here, or that this century-old library ever had an apartment in it at all, unless you already knew.