Why do we sentence people well past the human life span? (Photo: miss_millions/Flickr)

While "cruel and unusual punishment" is officially illegal according to the U.S. Constitution, convicted criminals still get sentenced to prison terms that no human being could ever serve.

Why sentence someone to hundreds or even thousands of years of incarceration when a simple "life without parole" would have the same effect? Sentencing laws vary across the world, but in the United States, the reason people get ordered to serve exceptional amounts of prison time is to acknowledge multiple crimes committed by the same person.

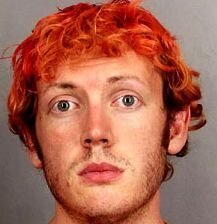

“Each count represents a victim,” says Rob McCallum, Public Information Officer for the Colorado Judicial Branch. McCallum is referring to the sentence handed down to James Eagan Holmes. In July 2012, Holmes opened fire inside an Aurora, Colorado movie theater, killing 12 people and injuring a further 70. Holmes was tried for two counts of murder for every person he killed. (In Colorado, you can be charged with two kinds of first-degree murder: murder "after deliberation," and murder "with extreme indifference." Due to the nature of his attack, Holmes was found guilty of both.) In July 2015, Holmes received 12 life sentences, and an additional 3,318 years for other, related crimes.

James Holmes is currently serving multiple life sentences and thousands of years in prison. (Photo: Wikipedia)

As McCallum emphasizes, each count against an accused criminal, especially in a violent crime, represents a human being, and each life lost deserves to be tried individually. Overlong sentences serve as much to bring justice to the victims as they do to dole out justice to the criminal.

While Holmes’ sentence is extraordinarily lengthy, it is not the longest in American history. That distinction goes to Charles Scott Robinson, who was sentenced to 30,000 years in prison in 1994. Robinson, of Oklahoma City, was convicted on six counts of child rape, and sentenced to 5,000 years for each, to be served consecutively.

Millennia-long sentences are not a uniquely American trend. The longest sentence ever asked for seems to have been leveled at a man from the Spanish island of Majorca in 1972. Gabriel March Granados had been a postman in the island’s capital city, Palma, but at some point he decided that he just wasn’t interested in delivering the mail anymore. According to the scant reports of the trial, Granados failed to deliver 42,768 letters—an impressive number considering he was only 22. He opted instead to open the mail and pocket any valuables. Prosecutors wanted to have him serve nine years per undelivered letter, amounting to a staggering 384,912 years in prison.

In this example, the sentence was meant to represent each of Granados’ individual crimes, even if they were as minor as invasion of privacy and theft. In the end, the judge settled on giving the man just over 14 years.

The longest prison term that actually got handed down is likely that of Thailand’s Mae Chamoy Thipyaso—"likely" because information is similarly meager. The wife of a high-ranking officer in the Thai air force, Thipyaso was apparently convicted of operating a pyramid scheme that bilked some 16,000 people out of hundreds of millions of dollars collectively. When the jig was finally up in 1989, Thipyaso and her cohorts were sentenced to 141,078 years in prison.

That's a small place to spend a few thousand years. (Photo: Global Panorama/Flickr)

These are just a few examples of seemingly outrageous prison terms, and there are many more that span hundreds or thousands of years. To those familiar with the inner workings of the law, they may seem an obvious part of the process, but to lay people, a 3,000-year sentence can seem strange. Ultimately, these multi-millennial sentences about rightfully acknowledging the injured parties—and making sure the punishment fits the many, many crimes.

This story appeared as part of Atlas Obscura's Time Week, a week devoted to the perplexing particulars of keeping time throughout history. See more Time Week stories here.