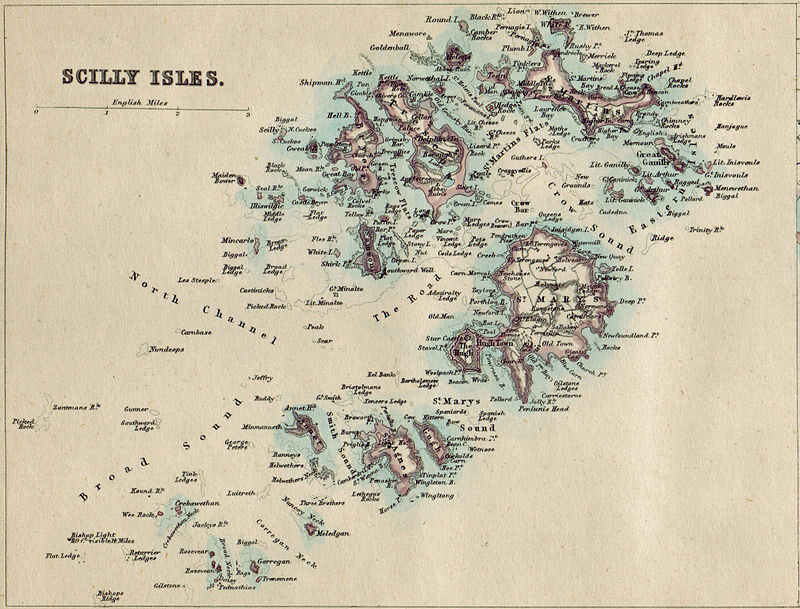

A 19th-century map of the Scilly Isles. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Some historians consider England’s Scilly conflict to be the longest war in known history, dragging on for a staggering 335 years. Yet one side was not a country in its own right, there were no casualties for the entire duration, and not a single shot was fired. Neither side even remembered they were still at war until someone checked the paperwork.

All of which begs the question: if war is declared but neither nation remembers, does it still count?

The Isles of Scilly are five inhabited islands and a multitude of other uninhabited rocks off the coast of Cornwall at the southwestern tip of England. With a population of roughly 2,000, the islands rely on fishing and tourism as the main sources of income. It is doubtful that anyone would consider them an international threat. Yet, somehow, they were at war with the Netherlands from 1651 until a mere 30 years ago.

Cromwell's Castle, a 17th-century fort, on the island of Tresco, in the Isles of Scilly. (Photo: Nathan Siemers/flickr)

To understand the origins of the 335 Year War, we need to go back in English history to the time of the Second Civil War (1642-1648), fought between Oliver Cromwell’s Parliamentarians and the Royalists, better known as the Roundheads and the Cavaliers. Cornwall was one of the last Royalist strongholds, but in 1648, it too fell into Cromwell’s hands. Britain being an island nation, it had one asset in its Navy, which had declared its support for the Royalists. And so, as the Parliamentarians swept across the country, the Navy was pushed further back until its only possible safe harbor was the Isles of Scilly. At the time, the Isles were owned by Sir John Grenville, a close friend of Prince Charles (later King Charles II), and therefore a staunch Royalist.

Meanwhile, across the English Channel, the Dutch were winning their independence from Spain in the Eighty Years War. The English had been allies with the Dutch since the war’s beginning, thanks to the protestant Queen Elizabeth 1. As the Netherlands gained independence they naturally wanted to maintain good relations with England, but with Civil War underway, they had to decide whom to support. Since it looked as though the Parliamentarians would overthrow the Royalists, the Dutch chose to ally with them. This included the support of the Dutch Navy. The Royalist Navy, down in the Scilly Isles, put up quite a strong resistance, seizing a number of Dutch ships and a great deal of cargo.

In the spring of 1651, Admiral Maarten Tromp of the Dutch Navy landed to demand reparations. Seeing that none were forthcoming, he reputedly declared war on the Isles of Scilly.

A painting showing the Siege of the Schenkenschans, part of the 80 year war between the Dutch and the Spanish. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Within a matter of weeks, a final push by the Parliamentarians led to the surrender of the remaining Royalist ships. The Dutch knew that they no longer faced any sort of threat and set sail for home. It seems they forgot one minor detail: the Scilly Isles weren’t technically a nation in their own right and so no one remembered to make the peace.

Years turned into decades, turned into centuries, and the war with the Dutch fell into local folklore. Generations passed on the tale that the islands remained at war with the Netherlands. No officials seemed to know if it was true or not.

Admiral Maarten Tromp of the Dutch Navy, who reputedly declared war on the Isles of Scilly. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Finally in 1985, a member of the island council and a keen local historian, Roy Duncan, decided to investigate the story for himself. He wrote to the Dutch Embassy, asking them to look into the matter. A response came back: after much searching, it seemed that no record existed of a peace treaty ever being signed. On April 17, 1986, the Dutch Ambassador visited the Isles of Scilly to sign said peace treaty, thereby putting an end to what is now fondly referred to as the 335 Years War.

Whether the declaration of war was legally binding remains in doubt to this day. Some historians argue that Tromp had no authority to declare war, and was simply blustering in the hopes of receiving compensation for damaged and lost goods. Furthermore, even if his declaration had merit, it surely would have been resolved in the 1654 treaty between England and the newly-formed Netherlands.

An aerial view across Tresco and the other Isles of Scilly. (Photo: Tom Corser/tomcorser.com/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 2.0 UK)

The ceremony marking the signing of the peace treaty in 1986 was more of a publicity move than it was an important event in international relations. Even Duncan admitted that the issue of the war had been “a joke for many years”. The signed declaration of peace remains on display in the Council Chambers in Hugh Town on St. Mary’s Island, and a quirky incident of British history has allowed the Isles of Scilly to lay claim to a place in the record books.