Couples dance in the Terrace Room of the New Yorker Hotel, from a 1930s hotel brochure. (All historical photographs: Courtesy of the Hotel New Yorker Archives)

New York is famous for its historic, glamorous hotels. But often overlooked, yet perhaps the most storied hotel of them all, is the one with the most iconic name: the New Yorker.

Its giant red sign dominates West 34th Street, and is often photographed as a city landmark, mostly on account of its name, yet the history of the New Yorker is largely unknown. Operating in the mid-level tier of hotels, it was never intended to be as upscale as the glitzier hotels of midtown like the Waldorf-Astoria, the Ritz Carlton or the St. Regis. The New Yorker was the hotel of the traveling salesmen, pilots and aircrew on short layovers, tourists and GIs being shipped to the European Front. In other words, if the Waldorf-Astoria were a well-dressed woman in an elegantly feathered hat, the New Yorker would be a salesman in a crumpled suit, drinking a whiskey and soda.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

A 1930s postcard of Hotel New Yorker.

Despite its slightly more humble nature, the New Yorker hotel is filled with untold secrets and forgotten stories—a beautiful Art Deco tunnel that ran from the lobby to Penn Station, still hidden underneath 34th Street; a vast private power plant that could have powered a small city; a gleaming forgotten bank vault underneath the lobby; an old dining room that came complete with a retractable ice floor, where diners could sip cocktails while watching a twirling glamorous dance show; and one of the world’s greatest inventors, Nikola Tesla, who died a virtual recluse after living alone in the hotel for over a decade.

Once New York’s largest hotel, its fortunes dipped with the neighborhood's decline in the 1970s. It has been abandoned, was nearly used as a hospital and a homeless shelter, and actually used as a church. We will be looking at the fascinating, untold story of the New Yorker hotel, through the efforts of one of its longest serving employees, a man who has steadily collected an astonishing archive of some 4,000 artifacts. These old cocktail lists, dinner menus, hotel blueprints, photographs from the hotel’s own in-house magazine and printing press, and recordings from its private radio station all tell of the golden age of one of New York’s most photographed and iconic buildings.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

A photo showing Abe Lyman and his California Orchestra .

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

A promotion for the "Tiger Stretch", an "invigorating morning 'workout,'" 1941.

My contact at the New Yorker is Joseph Kinney, who for decades has worked as the hotel’s Senior Project Engineer, although his unpaid job as unofficial historian has been just as consuming.

When we met in the lobby of the hotel, he explained how the character of the establishment was always going to be defined by its location. Situated on a city block of Eighth Avenue between 34th and 35th Streets, adjacent to Penn Station, it was designed as a hotel for the travelers and workers coming into Manhattan from the station, from the Port Authority bus terminal a few blocks north, and from the west side docks.

When the New Yorker opened on January 2, 1930, it was designed as one of the largest, most sophisticated and technically advanced hotels in the world. Kinney showed me in the archives the original 1930s brochure, describing the new hotel as a “Vertical Village”, laying out why this was the queen of modern hotel living.

Its 43 stories resembled a self-contained town with 2,500 rooms. The kitchens were staffed by 135 chefs, 23 elevators raced upwards at 800 feet per minute, its own switchboard was manned by 95 phone operators, while nearly 80 feet underground, its own power plant, the largest in the United States, was big enough to generate power for a city of approximately 35,000 people. The New Yorker had a 50-chair barber salon. It proudly boasted not only a radio in every room, but a private radio station. In addition to providing in-room entertainment, the radio station broadcast big-band music from the Terrace Room live across America.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

The Terrace Room in the 1930s.

By 1948, the New Yorker had more televisions under one roof that any other building in the world. The food was held in such high regard that the hotel was commissioned to operate the dining services out at LaGuardia Airport, in the charmingly-named Kitty Hawk Bar and Grill, and the Aviation Terrace. During the war, the hotel thronged with service men who were given a few days' stay as guests before boarding the steam liners for Europe. So beloved was the New Yorker hotel to soldiers that many photographs exist from the Western Front with dugouts daubed “Hotel New Yorker” on the entrance.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

A WWII dugout named Hotel New Yorker.

But for all its state-of-the-art, futuristic facilities, the New Yorker was doomed almost from the beginning. As soon as it opened, the hotel was immediately confronted with the harsh realities of the Great Depression, and a lack of paying guests. Trying to weather the fallout from the Wall Street crash just months before, the hotel was already a relic of the bygone roaring ‘20s. The hotel’s first general manager, Ralph Hiltz, in an effort to make the place seem alive and well, would order all the room lights on at night. But it was a thin ruse. “The hotel really struggled. It never really got over it,” says Kinney. By 1966, the New Yorker had filed for bankruptcy.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

A woman waits in the mezzanine lobby in the 1930s.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Another brochure photo from the 1930s, showing two women taking tea.

In a city known for its glamorous thoroughfares, Eighth Avenue today has retained the slightly seedy air of old New York. The stretch between the new Penn Station and the Port Authority is still littered with peep shows, methadone clinics, and low-rent retail stores, that resemble the grittiness of 1970s Times Square, and rising above it all, the Art Deco beauty of the New Yorker.

Having worked in the neighborhood for 10 years or so, I’d often noticed on the New Yorker’s exterior, a beautiful, highly ornate brass door, next to the always-closed Tick Tock Diner. Labeled with the name “Manufacturers Trust Company,” the elaborate Art Deco styling wouldn’t have looked out of place on the Chrysler Building. Kinney explained how a bank had been built as part of the original building but had long since shuttered. The blueprints in his collection show the stunning original bank doorway as well as the vault still sitting underneath us.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

The grand north lobby.

Walking through the lobby, Kinney tells of how, in the New Yorker’s original heyday, one of the first things visitors would have encountered was a bellhop, who attained advertising immortality. It turns out that this bellhop, Johnny Roventini from Brooklyn, was also shilling Phillip Morris. He would walk through the lobby loudly issuing a “call for Phillip Morris.” Interviewed by the New York Times, Roventini recalled how the odd phrasing sounded: "I went around the lobby yelling my head off but Philip Morris didn't answer my call." The campaign proved a huge success, and the bellhop’s call became a successful ad campaign.

We passed through the lobby to a small staircase to the left of the reception desk. At the foot of the stairwell was a wrought iron fence marked “MTC” and the giant vault. This is what remains of the old Manufacturing Trust Bank, Kinney explains. Inside the vast safe was a long wall, containing the original safety deposit boxes—thanks to the bank’s terrible timing, launching during the Great Depression, these were rarely filled. Plans are underway to turn the old bank vault into a bar, similar to the vault bar underneath the Trinity Building in lower Manhattan.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Underneath the lobby lie the original bank safety deposit boxes. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

Around the corner from the bank door, on the 34th Street side, is the home for Al-Jazeera television. Another ornate, gleaming, revolving brass door leads onto the studios. But this was once one of the most glamorous night spots in the whole city: the Terrace Room.

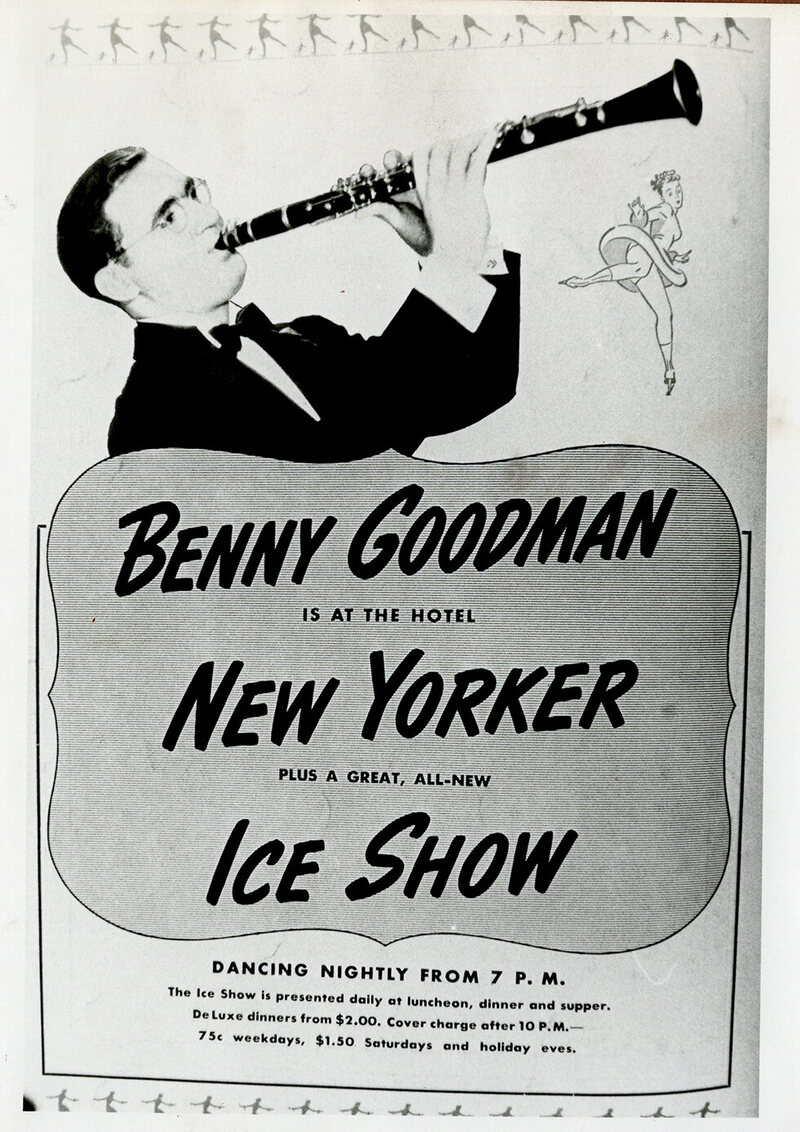

Named for its terrace floors, the original hotel brochures describe how “World-famous orchestras interpret the syncopated rhythms of today nightly through the dinner hour and during supper in the Terrace Restaurant.” Benny Goodman, Glenn Miller, Woody Herman and Bob Crosby all played here. The concerts were broadcast four nights a week to millions of homes across the United States by CBS radio, and across the European and Japanese theaters of war by the American Forces Network.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Advertising for Benny Goodman and the Ice Show.

Incredibly, we can listen in to the original sounds of the Terrace Room, for saved in the archives are the recordings, on glass discs, stamped with their own record label, the Hotel New Yorker. “Good evening ladies and gentleman,” a velvet voice croons, “this is Bob Russell from the Radio Control Room of the Hotel New Yorker.” The crackling swing music takes us back to the golden age of New York hotel supper clubs, and the tinkle of cocktail glasses. Drinks such as the New Yorker Special (peach, Italian vermouth, dry gin, curaçao, orange peel, tokay grape) once cost a mere 35 cents.

Even more remarkably, the terraced floors led down to an actual ice rink. The focal point of the Terrace Room was a retractable ice floor, where diners could enjoy the Hotel New Yorker Ice Follies' "gorgeous girls and foremost stars of the flashing blades” while dining on such delicacies as “baked filet of sole Waleaska with lobster ($1.15)” or “breaded veal cutlet Holstein, fried egg and sauté potatoes ($1.30)”, although, the menu noted, “because of rationing, we can only serve one cup of coffee with any meal”.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Spectators watch the ice show at the New Yorker Hotel.

This rink was constructed in sections of refrigerated flooring 20 feet long and four feet wide that retracted and automatically stacked underneath the band stand at the North End of the room.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

The ice show in full swing, in 1947.

Today, thousands of tourists and New Yorkers walk by the bustling corner of Eighth Avenue and 34 Street not knowing that here their predecessors enjoyed one of the most glamorous evenings on the planet, dancing to Benny Goodman while watching a spectacular ice show.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

The extensive Manhattan room cocktail list.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

The menu from May 23, 1941.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

A card advertising astrologer Ronda, who promises an "entertaining personality reading".

But underneath the old dance floor lies something even more remarkable and secret, as Kinney and I head deeper underground. One old brochure in the archives was headlined “So Convenient!” along with a map of midtown Manhattan, which proudly noted that one of the leading amenities of the hotel is a “private tunnel linking the New Yorker to Penn Station.” Drawn on the map was a depiction of an underground pass leading from the hotel to not just Penn Station, but as far as the Empire State Building.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

A brochure for the New Yorker, including a map showing the hotel's private tunnel to Penn Station.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

The tunnel in the basement of the New Yorker, which led to subway lines and Penn Station.

I asked Kinney about the brochure, and whether this mysterious tunnel was ever actually built. “Sure”, he says, “Would you like to take a look?”

We go into the basement, to a sealed door, and beyond into the tunnel itself, which is filled with excess old hotel fittings, chairs, carpets, and beautiful Art Deco tiling. Walking into the tunnel, Kinney explains that we were now directly underneath 34th Street. In a zig-zag shape, at the far end was the same brass door of the photograph, that would lead today onto the platform near the E line. The MTA blocked the other side off sometime in the 1960s, so this was as far as we could get coming from the hotel.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

The secret New Yorker tunnel underneath 34th Street. This once led directly into Penn Station. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

The beautifully tiled Art Deco tunnel hidden underneath 34th street. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Couples on the balcony in the 1930s.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

The Art Deco interior of the hotel's beauty shop.

Wending back through staircases far out of the reach of the hotel guests, we ended up at around 80 feet below the sidewalk, at the remnants of the New Yorker’s private power plant. A vast undertaking, the DC generating plant was the largest private one of its kind when it was built in 1929. It was powerful enough to provide electricity for a city of 35,000 people. The motors were controlled by a 60-foot switchboard. This power plant was so remarkable that the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) designated the New Yorker Hotel as a “Milestone in Electrical Engineering”, on par with the Niagara Falls hydroelectric plant. You can still see the operating switches for the skating rink, “north ballroom parlors A, B & C” and coffee shop lights, ghostly reminders of the hotel’s glamorous past.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

The old power plant in the basement could generate enough electricity for a small town. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

One of the most famous men of the 20th century once worked in this subterranean world. In 1933, Nikola Tesla moved into the New Yorker hotel, occupying rooms 3327 and 3328 until his death in 1943. Kinney speculates that Tesla chose the hotel because it was the most technically sophisticated of its time. While a guest there, he would go downstairs to spend time with the generator's engineers, and Kinney speculates, tinker with the plant.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

The hotel's barber shop.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Beulah Gage washing the windows of the hotel.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

The New Yorker's in-house weather reporter, Emerald O'Day.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

New Yorker staff with the hotel Christmas tree, 1944.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

A music request card.

Our next stop was to the rooftop of the hotel, where we got a close-up look at the iconic red sign. Twenty feet high, it is one of the largest signs in the United States. This landmark, though, almost disappeared along with the hotel. As the fortunes of the Eighth Avenue neighborhood plummeted in the 1970s, the hotel finally closed in April 1972. Plans to turn the Art Deco gem into a hospital faltered and by 1975, it was finally abandoned.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

The original hotel recordings from the Terrace Room where some of the biggest names in Big Band music once played. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

This overlooked Art Deco door, long since closed, once led to the bank in the hotel lobby. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

The hotel was saved by an unlikely source: the Unification Church who bought the hotel in 1976 to use as their world mission center. In 1994, the New Yorker reopened as a functioning hotel. It is now operated by the Wyndham group, with over 1,000 rooms open.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

From 1939, photographs of the hotel's big band.

Part of the New Yorker’s revitalization has been its embrace and celebration of its Art Deco heritage. Artifacts from Kinney’s meticulously collected archive are on display in the lobby and in a small adjacent museum, where visitors can experience the golden era of the hotel, while listening to the big bands who once graced its ballrooms.